Some Concerns With Metamodern Theory

Mostly concerning postmodernism.

On Substack, there have been a couple of articles and at least two notes I've seen over the past week or two discussing metamodernism. Which, on Substack, is basically considered trending. And it was employed well in all of those, making for some pleasant reads. I like metamodernism a lot, or at least I find it interesting, and I was very into it for a while.

I think I’ve read most of the published literature on it, from the experimental Brendan Graham Dempsey spirituality series to the pseudonymous Hanzi Freinacht works and numerous articles, both peer reviewed and blog-style. I really have tried to keep up with the community, which, overall, I find interesting.

That said, I don't know exactly how I feel about it.

I’ve noticed some common trends that seem a bit problematic. I’m not going to say these are ubiquitous, but they’re recurring enough to catch my attention.

Metamodern Overview

If you don’t know, metamodernism is an epochal framework—an emerging philosophical structure or cultural theory that’s characterized by ten tenets (and eventually a few more were added, though they’ve been less popularized) which I’ll summarize here:

Oscillation between Modernism and Postmodernism1

Dialogue over dialectics

Paradox

Juxtaposition

Collapse of distances

Multiple subjectivities

Collaboration

Simultaneity and generative ambiguity

Cautious return to metanarratives

Interdisciplinarity

A quick and dirty way to summarize it is this: modernity is understood as a kind of naïve era, postmodern is skeptical and non-naïve, metamodern is a cautious, informed, selective return to naïveté, while still retaining non-naive awareness and skepticism.

Modern → Postmodern

Alright, so what’s meant by modernity being considered naïve?

Well, assumes a belief in progress, in the autonomy of the individual, in the idea that we can conquer anything. There are all these promises tied to modernity, especially Enlightenment-era promises. You could think of modernity as the optimistic, humanistic era, wherein the autonomous individual was liberated from the chains of premodern worldviews, and poised to conquer the world.

This mindset is reflected in the (in)famous “God is dead” statement by Nietzsche, who was really just capturing what he saw as the broader sentiment in Europe at the time: that they’d moved past the necessity of God.

But as this idea develops, some people start to think: look what actually happens with all this progress. In the 20th century, even though you might argue that people are generally more peaceful or more tolerant, and we seem to be moving teleologically toward a more liberated and prosperous society, there are still massive, mind-boggling exceptions.

For example, there’s less global conflict on the whole, but the global conflicts that did happen included two world wars, multiple genocides resulting in the near-erasure of entire generations from the 19th-20th centuries.

Thus, the postmodern movement emerged, primarily from France, offering these challenges and more. Not only were modernity’s expectations misplaced, so was its self-image, and even the idea that people were generally more peaceful and tolerant.

Who were these nay-saying Frenchmen?

Well, to borrow Foucault’s framing: if you wanted to be an intellectual in France at that time, you had to be conversant in both Marxism and semiology (semiology/semiotics being the study of signs). So, prior to being “post-” anything, they were just a regular ol’ bunch of semiologically-literate French Commies.

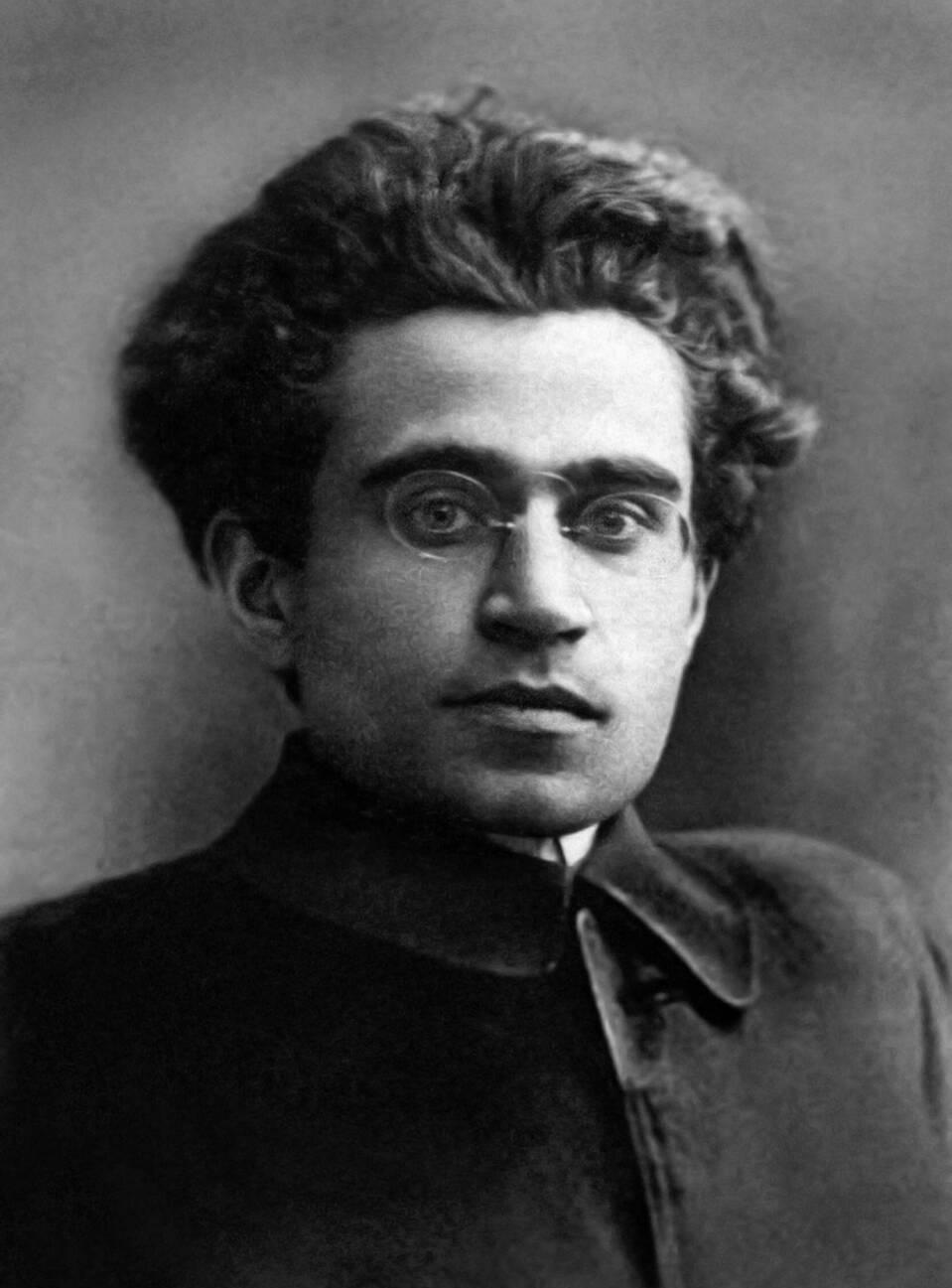

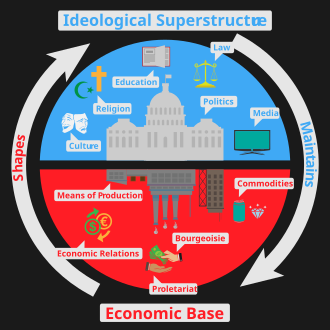

No small amount of these French Commie’s inclination to “read culture” so pessimistically was cultivated, if not seeded, by Antonio Gramsci, the early 20th-century Commie prisoner who Marxizes idea of hegemony.

If you recognize the term, it’s because he borrowed it from the decidedly less French, less Commie, Greeks. For him, the capitalist system is a hegemony which conditions common sense to fit the worldview of those in power.

In the case of modernism, the idea that we are progressing from something toward something else (teleology) is taken as a given, and therefore conditioned by the hegemony.

Now, the extension of Marxism beyond the economic is something that’s been both lauded and critiqued by Marxist scholars. Jean Baudrillard has a particularly thoughtful critique of this in Utopia Deferred, which I won’t get into here. But for the most part, the idea caught on—in both Marxist thought and the post-Marxist developments that would eventually turn into postmodern thinking.

What we start to see is a questioning of everything, from the so-called myth of progress all the way to teleology broadly, including that of Marx,2 and by goodness, they even take cracks at Reason (capital “R”) itself, the golden calf of modernity.

Jean-François Lyotard, in The Postmodern Condition, describes postmodernism as an incredulity toward metanarratives. He champions the petits récits—the small, local narratives. He wasn’t necessarily making an ontological or metaphysical claim here, but more of a cultural observation about the times: the postmodern sentiment moves beyond grand narratives and into the particular, the contingent, the fragmented.

Michel Foucault as postmodern exemplar

The way this gets employed by postmodern thinkers often goes something like this: “You say our society is advancing from savagery to rationality, but look at the savagery we’re still engaged in.”

Take Foucault’s Discipline and Punish. It’s a widely cited critique of the prison system and serves as an exemplary case.

What he’s tracking there is the shift from overt physical violence, like cutting off a thumb or branding someone for a crime, to what appears to be a more merciful system: incarceration. Obviously, people were imprisoned all throughout human history, but Foucault points out that prison was understood more like we today understand jails: a temporary placement while awaiting punishment, not the punishment itself.

He argues that this isn’t more merciful at all. The intent was to shift from punishing the body to transforming the soul. Once the prison system was stripped of its Christian optimism, it no longer aimed to produce morally transformed individuals, but neither did it have the chutzpah to openly admit to a desire to punish, so it settled on semi-veiled punishment in some conversations, and a great deal of control in praxis.

So you end up with this strange in-between system that’s neither committed wholly to retributive justice nor genuine transformation. Its aim, for Foucault, was controlling prisoners and making sure they knew they were under control. And this is done through various mechanisms—most famously, the panopticon.3

In fact (and this is a bit of interpretation on my part, but a nice little nod to metamodernism), we might say that the prison system oscillates between retribution and transformation (or holds them both in tension, I don’t know). To Foucault, society acts like imprisonment is merciful and natural, when it’s really fairly modern, and mostly about crushing the soul and conditioning people to believe they can never again be unobserved or uncontrolled. And somehow, that’s presented as less savage than cutting off a finger or giving someone a beating.

The psychological torment of the prisoner is a kind of demonstration of sovereign control, disguised as more refined than the barbaric practice of flogging. And, I mean, he has a point; who comes out of prison saying, “I neither committed acts of violence nor saw acts of violence”—nobody that I know, anyway.

What? We’re more civil because we defer people to a place of both control and violence, and so long as we don’t have to get our hands dirty with openly admitting we’re okay with violence being done to them? Well, we’re some real heroes!

In Madness and Civilization, Foucault traces cultural shifts in scapegoating. For example, the idea that the witch-burning of the early Modern era (yeah, that’s right, the Middle Ages get blamed for a lot that actually emerged in the Renaissance)4 was overt violence, done to an out-group. As you might guess, Foucault didn’t entertain the idea that there were actual witches (nor were they the only example), but rather that they were necessary as scapegoats to satisfy the cultural need for violence in service of power.

Foucault argues that our culture still has similar scapegoats; we just shift who qualifies. He shows how the focus shifted from heretics to the insane. State power reallocated its mechanisms from suppressing heterodoxy to managing the mad. For Foucault, society can’t help but establish power structures keen on sticking it to the Other,5 it’s basically our favorite thing to do.

These are a few examples, specific to Foucault, but the general idea here of questioning modernism is central to most postmodern critiques. Many of these critiques also revolve around the ontological "Other," in a related, but not identical way to how Foucault’s did. Such was the case with non-postmoderns who emerged from similar Marx/Freud thought traditions as well (Emmanuel Levinas or Jacques Lacan, and so on).

Postmodernism, the movement.

The Marx/Freud types, the postmodern types, emerging from similar places with similar references and frames of thinking. Marxism was a decidedly Modern form of thinking, but it was also a subversive movement within modernity.

The thinkers who succeeded Marx are also operating from within Modern superstructures, which the postmodernists would gut like a fish, then turn against the superstructures.6 So postmodernism, understandably, becomes hard to define. It’s a subversive movement living in the bones of a subversive movement that’s also living in the bones, with some meat, of modernity. It’s not a school, it’s not even really a movement. It’s (and here’s another nod to our metamodern friends) a structure of feeling.

Postmodernism was, in my estimation, more a shared sentiment more than a coherent project, not that anyone’s really making a different arguing, including Lyotard. The figures involved were disparate in ways that aren’t always (though sometimes are) neatly categorized as different roles on the some project. Yes, yes, they often had similar training or intellectual backgrounds, and even had similar modes of expression sometimes, but their goals diverged significantly… you know, sometimes.

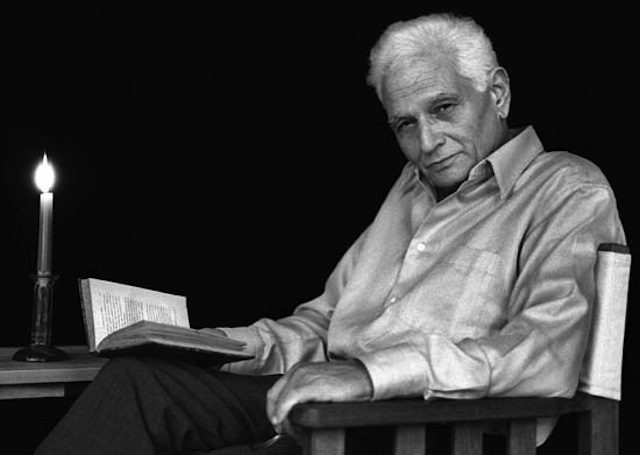

Derrida’s aims, for instance, are almost incomparably different from those of Deleuze and Guattari. Lyotard’s own classification of “postmodernism” was rejected by many of those he grouped under it.7 Foucault, probably the central figure (or at least the most famous at the time… and probably now) was pursuing a very different kind of inquiry, focused on the dynamics of power, which we find as central focus in not-as-many-as-you’ve-been-told non-Foucault, postmodern works. Baudrillard (who’s my favorite) was working in his own strange orbit, waaaay off to the side of the rest.8

So yes, there’s a lot going on in postmodernism, but if you had to unify it, incredulity toward metanarratives is probably about as close as you could get to a common thread.

To return to the ontological Other, if the metanarrative is what unites a group of folks cross-culturally/temporally, the postmodernist would often (but not always) be interested in the folks not united. Again, while many people benefitted from the disintegration of monarchical powers in Europe, many were left off as bad as before or worse.

Postmodernism often (but not mostly) asks, what about the people left behind? The mentally ill, the enslaved, the colonized, the silenced, the women, you know, all the people the folks we consider woke are so interested in these days.

If, according to many (but not all) postmodern thinkers, there’s progress, then for every two steps forward, there's (often, but not always) a step back.9 Or as is often the case, lateral moves are confused for upward ones. Either way, postmodernism insists on challenging the framing itself.

If modernists are the prophets of Baal, postmodernists are Elijah.10

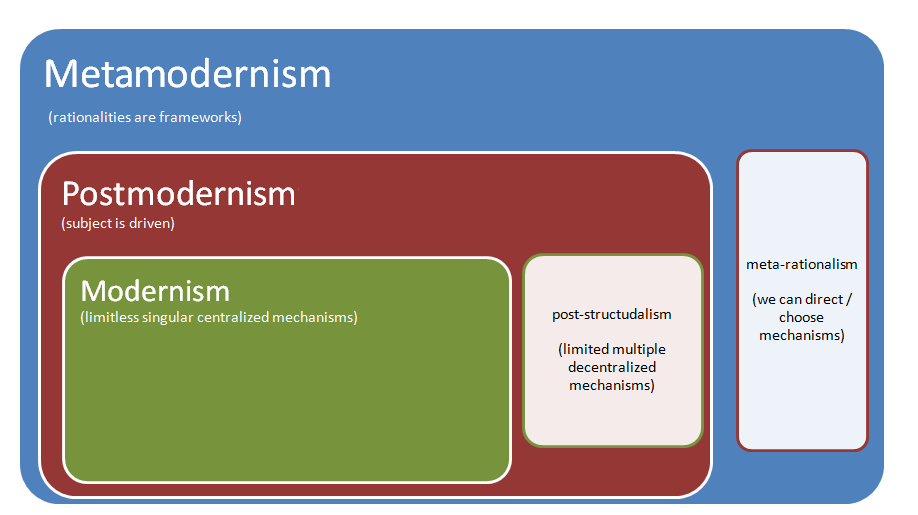

Metamodernism’s dealing with postmodernism

That’s all fair, and I think most metamodern thinkers would mostly agree that I haven’t gone grievously awry so far. But where metamodernism, I think, steps in two scoops of poop is with its reliance on these sorts of broad, somewhat flattened, characterizations of postmodernism which I’ve just offered. But, notice how many things I had to put in parenthesis to hedge my statements? That’s the sort of animal we’re dealing with here.

Metamodernism, as commonly described, is the oscillation between modern and postmodern sensibilities. It returns to the naïveté of modern thinking, but with enough postmodern awareness to avoid its pitfalls. It's a contradictory posture that requires a kind of back-and-forth between modern sincerity and postmodern skepticism.

To spot these oscillations, it’s necessary to have a mostly fixed idea of postmodernism.

One such example is the focus on the form of postmodern communication—irony, sarcasm, skepticism, detachment. This is important to the metamodern movement, because postmodern communication represents the “ironic” layer in “ironic sincerity.”

The metamodern subject expresses themselves through this ironic sincerity, using irony as a mask for sincere sentiment. Think of phrases like “That’s low-key wholesome.”11 The phrase includes ironic distance (“low-key”) but also earnest appreciation. Sincerity, for the metamodern, needs to be softened or veiled, since unfiltered sincerity is considered too darn naïve.

I think that’s a fair way to describe some cultural expression today. And that’s part of why I find metamodernism compelling.

However, the idea that postmodern communication is best-characterized as primarily ironic or sarcastic seems to be a bit reductionistic. While you can fairly describe a great deal of postmodern dialogue as irreverent and ironic in tone, and indeed, it often deals with “sacred” ideas with such irreverence, it’s not as though the primary style of communication in interviews, debates, and even writing, was ironic, distant, or sarcastic. They were, in many circumstances, prone to that sort of thing, but plenty of non-postmodern rebellious upstarts who preceded them were as well. Freud was irreverent, but less sarcastic. Nietzsche is a tough example, since many consider him the first postmodern philosopher, but he was that way too. And, very tellingly, 19th-century European and Russian youths, especially of the nihilistic bent, were perceived as similarly tempered.

Indeed, there’s plenty of irony and detachment in figures like Baudrillard or Foucault, but there’s also a great deal of sincerity. In fact, I’d argue, as others have, that Baudrillard was a sentimentalist. He had a real affinity for the premodern that many have picked up on. There’s a sense of yearning and mourning that’s often presented plainly in his texts, though less so in his interviews.

Foucault, too, often argued that the modern world isn't obviously better than the premodern. I wouldn’t call him a sentimentalist, but you can find a similar impulse in his work; an acknowledgment that no era has gotten it right. In that sense, you could read him as a sort of reluctant defender of the premodern.

Derrida is also often misunderstood. When people talk about deconstruction, they act like he’s just trying to tear everything down. But he’s really trying to complicate binaries because he sees them as never quite having gotten things right, and he thinks/hopes to do something about it. If deconstruction were a negative term, rather than a “complicating” term, he’d seem more irreverent and distant. But it’s not the opposite of construction, it’s not to take things apart, and he hoped it could be prescriptive to the world in a sincere way, even if his presentation was often more cutting than sweet.

Binaries

This ties into another issue: some metamodern writers have, a few times at least, characterized postmodernism as focused on binaries, presenting metamodernism as transcending that focus. True, there was some interest in binaries, but not in a pro-binary way. The whole point was to problematize binaries, not to reify them.

In fact, to be post-structuralist (subset of postmodernism, focused on challenging the structuralist semiology) was expressed in ways that were often focused on the explicit problematization of the signifier/signified binary. Baudrillard touched on this, Barthes complicated it in his later career, and Derrida beat it up with deconstruction.

The strategy of deconstruction was to show that in any binary—man/woman, light/dark—one term is privileged over the other. The goal wasn’t to flip the hierarchy and leave it flipped, but to destabilize the binary itself. In our current pseudo-postmodern culture, the woke seem to stop at the inversion: women are better than men, oppressed over oppressor, etc. But deconstruction wanted to go further and introduce a non-dialectical third term that renders the original binary incomplete or irrelevant.

This approach is far more nuanced than saying “postmodernism was obsessed with binaries.”

If anything, rigid dualism is more visible in traditional Marxism. Foucault often structured things in terms of power and resistance, but even he didn’t insist on fixed dichotomies. Take his debate with Chomsky—he concedes that power structures may be inevitable. He doesn’t argue, like a strict Marxist might, that they must be abolished.

I mean, Marx was a Hegelian, right? He took Hegelian dialectics and made it materialist, right? Well, dialectics deals with the resolution of contradictions via the aufhebung of the terms, which begets further binary entanglements. Foucault and Derrida were very keen on escaping the clutches of Hegel, not affirming them. To that end, Foucault said:

Truly to escape Hegel involves an exact appreciation of the price we have to pay to detach ourselves from him. It assumes that we are aware of the extent to which Hegel, insidiously perhaps, is close to us; it implies a knowledge, in that which permits us to think against Hegel, of that which remains Hegelian. We have to determine the extent to which our anti-Hegelianism is possibly one of his tricks directed against us, at the end of which he stands, motionless, waiting for us.

Nihilism

That brings us to a major critique of postmodernism by its contemporaries, which I also see as implied by metamodernists: its perceived nihilism. Marxists have often accused postmodernists (who were post-Marxist) of offering no real alternatives, just endless critique. “There’s no way out,” they’d say. In that sense, you could say the modern, if you associate that with the Marxist, is the optimist, while postmodernists become the pessimists.

Hence, the “non-naïve” posture that metamodernism associates with postmodernism in its oscillations.

I can see that in some ways, but again, I don’t know that it’s entirely accurate. Foucault himself seems to oscillate between naïveté and skepticism.

In the Chomsky debate, he explicitly says he prefers to critique from within, rather than propose new systems. But that doesn't mean others in the tradition weren’t prescriptive or didn’t look for ways to subvert the system, as a more traditional Marxist might. Derridean arche-writing, Baudrillardian fatal strategies; there’s probably more.12

Metamodernism is often spoken of as this fertile ground where we might build the world anew. That is, now that we’ve shed the stagnancy of postmodern [ ]—I leave the brackets blank because I’ve never seen postmodernists called nihilist in metamodern literature, but I see it as implied in setting postmodernism up as the contrasting term in a dialectic where the other side is represented as the side able to be mobilized toward positive social action (e.g. activism).

Overall, in a lot of metamodern literature, there’s a strong desire to move past the postmodern in order to begin the “metamodern.” This necessitates some sort of fixed idea of postmodernism, so there’s a need to rely on these kinds of abstract characterizations, which are mostly fair, but sometimes not.

But in my view, this doesn’t do justice to postmodernism—in fact, the very act of omitting those little differences/details which are excluded from the abstraction “postmodern” is, in itself, anti-postmodern.

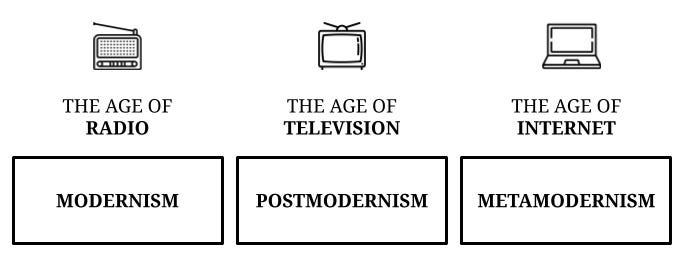

Metamodernity as Epoch

My second major critique has to do with the epochal framing. Terms like postmodernism/postmodernity, modernism/modernity, metamodernism/metamodernity are often used—well, not quite interchangeably—but in ways that don’t always capture the differences in meaning. Namely, that “ism” refers to a cultural movement, “ity” refers to an epoch or era in history. I see the confusion, since “ism” can define an “ity",” but still.

Metamodernity is generally presented as an emergent era, following the postmodern era. But, and I know I can’t lay blame for this characterization primarily at the feet of metamodernists: it doesn’t seem clear that postmodernism is an epoch or era, rather than a movement within the late Modern era.

An epoch, as it’s been used as historical shorthand in the past, is a sweeping thing. modernity works. It defined Western civilization and reshaped the globe. It wasn’t just an intellectual movement that impacted some sections of several universities and then dripped into the culture for 30-50 years non-comprehensively. It permeated life near-ubiquitously. This is why we can speak of “the Western medieval mind” and know that, with exceptions, we’re going to capture the serfs, the kings, and it’ll transcend language, nation, and even religion.

To be clear, I think the Digital Age can achieves that, but I’m unconvinced that postmodernism achieved it… unless you consider where we’re at now to be postmodern. You see the issue.

When, exactly, was the Postmodern era?

Postmodernism started as a French intellectual movement, made its way into universities, and filtered into broader culture through niche avant-garde scenes. It hit its stride in the broader culture in the 1990s. You can see it in South Park and similar media—but even then, its reach was uneven.

I worry we’re retroactively labeling a short, often urban cultural moment as an entire era. Not all ’90s culture was Rage Against the Machine. Full House aired at the same time as South Park, and it was hugely popular. The Simpsons showed less irreverance than South Park, but certainly had some. But it oscillated between this and the very Modern nuclear family wholesomeness; is this a simple precursor to metamodernity within the apex of postmodernity, or did postmodernity never quite have the whole of the culture?

This is the problem with calling it an epoch—when exactly was postmodernism the broad cultural sentiment, the backcloth that defined us? An epoch is supposed to reflect generational turnover. But during this postmodern “era,” generations overlapped, with parents and grandparents still being formed within a modernist framework, and just when the youth was captured by the epoch in its fullness, the 21st century rolled around and the epoch switched. This seems unlikely.

If we’re honest about it, for every Unabomber critiquing modernism, you had others fully embodying it. Did most people really stop believing in the all-pervasive powers of science/progress/human ingenuity during the 20th century? Not a chance! The belief that science could solve all our problems persisted deep into the century.

Even in the ’90s, critique of capitalism was growing, but mostly at the economic level, where the postmoderns had gone far beyond that. Widespread skepticism of science and reason didn’t become mainstream until the last decade or so, if that. You can tell this was the case because that’s when the New Atheist movement began to decline as well.

Were the culture clearly beyond the humanistic optimism of the sciences by the turn of the 21st century, then by the 2010’s, how could the New Atheists not have gotten the memo? Moreover, how could they have gained so much traction? No, it seems clear that were caught off guard by the rapid shift in sentiment in the late 2010’s/early 2020’s.

The New Atheists were like the arriere garde of the Enlightenment. Remember that Japanese soldier, Hiroo Onoda, who was part of the Japanese Imperial Army during WWII, and kept fighting in the Phillippines until 1974 because nobody told him the war was over? The New Atheists were like that guy.

A postmodern epoch preceding the ~21st century shift to something new, would have to have achieved its grip and begun dissipating by the early 2000’s to make room for the next thing (metamodernism, post-postmodernism, etc.). But it never seems to have achieved that grip.

Rather, Charles Taylor’s “Nova Effect” seems to characterize the 90’s pretty well. For Taylor, the secularization of modernity led to a constellation of options. That is, it’s not that culture is all atheist or irreligious, but that the secular Modern society assumes a plurality of options. God is one option among many, your political view is one among many, and so on. The simultaneity of culture-gripping Enlightenment avatars and postmodernists and premodernists (like me and probably my boy Baudrillard) seems to work better in this framework.

Postmodernism, after all, was working within the bones of Marxism, which is a Modern movement, part of the constellation of possible Modern movements. It’s a subversive one to be sure, but still within the structure it critiques (don’t take my word for it, being/speaking from within the hegemony is a longstanding problem for Commies).

I don’t think you can say the same about modernity in relation to the Middle Ages.

The Renaissance, I don’t know, take your pick; I’ve heard it called a movement within early modernity, I’ve heard it called an era. Whatever it was, it gave us broad artistic, theological, and philosophical realignments throughout Western civilization. Something structurally new emerged with new emphases, and began the work of re-staining the backcloth of the medieval mind.13

That might be happening now, as a result of the Digital Age, but seems suspect with the postmodern movement.

So, I wouldn’t be all that upset to concede that postmodernism is a late Modern movement, or that postmodernism is an early Metamodern movement—if we concede that metamodernism is a movement representative of an epoch, which is still suspect.

Jean Baudrillard

Again, these broad epochal categories reliant on definitions that are relatively broad, though fixed, and treated as working models are necessary for metamodernism, I get it. These are used to deal with the acknowledged complexity and fragmentation of postmodernism. Which is fine in shorthand reference, but in post-postmodern theory formation, seems to often fall into the trap of insufficiently grappling with the complexity itself.

That leads into what I want to discuss next, and have been wanting to talk about this whole time: the work of Jean Baudrillard.

See, as a card-carrying Baudrillardian, I think it's questionable whether we're dealing with epochs at all.14

Note: I say this as someone who wants to see metamodernism succeed. I think the framework is broad enough to absorb critiques like mine, just as it absorbed Raoul Eshelman’s “performatism” in what I’d say was a fairly successful way, even extending it. Brendan Graham Dempsey, for instance, extends the idea of “artistically mediated belief” to “aesthetically mediated belief,” widening the lens to include broader cultural phenomena. That’s a good move.

But when it comes to Baudrillard, I think he’s a difficult fit; he doesn’t integrate neatly anywhere.

Baudrillard’s central theme for most of his career was simulation—not in the digital or computing sense necessarily, though these are examples of simulation—but as a cultural condition. He critiques the idea of a superstructure in the traditional Marxist sense,15 but nevertheless describes something akin to it: a cultural matrix that mediates all perception.

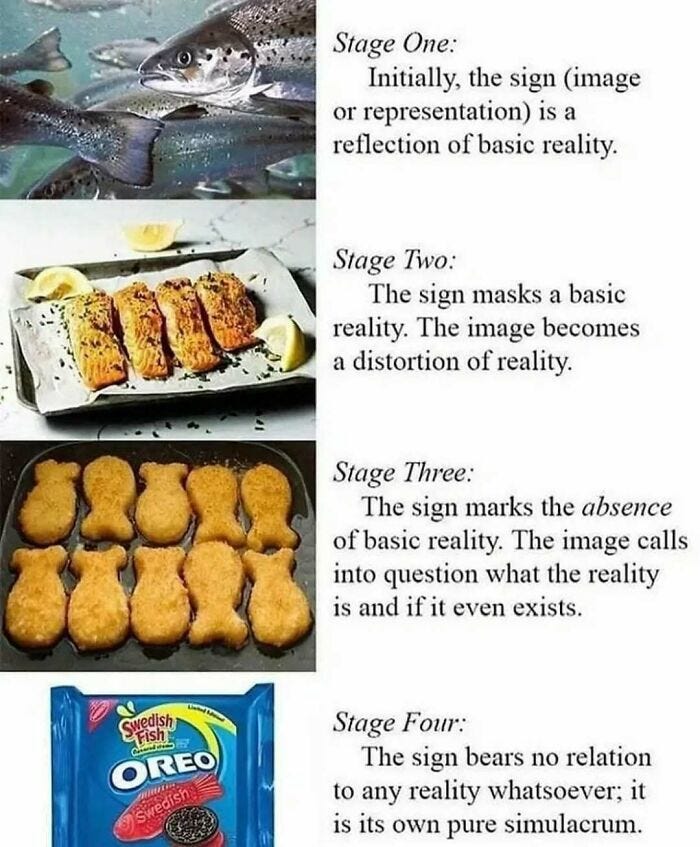

To understand it, you can start with classical semiotics: the signifier (the word “tree”), the signified (the concept of a tree), and the referent (a physical tree in the world). Baudrillard, especially early on, identifies nature as the "arch-referent," the grounding reality to which things once pointed. And he laments that we’re losing (or have lost) contact with it.

The precession of simulacra, as he lays it out, goes in four orders:

First-order simulacra aim to faithfully replicate the real. A statue meant to look lifelike would fall into this category.

Second-order simulacra begin to distort the original. Think of Buddy Jesus from Dogma—a caricature of the traditional religious figure, built with self-awareness and irony.

Third-order simulacra hide the fact that they have no original. An example might be the image of a white, blue-eyed Jesus. There’s a historical figure behind the tradition, yes, but the dominant image in much of Western iconography doesn’t represent him. It presents itself as a historical likeness while having no accurate referent.

Fourth-order simulacra no longer even pretend to have a basis in reality. They are simulacra-proper; completely autonomous. Take Santa Claus as we know him today: jolly, red-suited, flying reindeer, you know the guy. That figure is a synthetic amalgam of unrelated myths, advertising things, and folk remnants. There's a real Saint Nicholas in the background, like way way back there (like 325 A.D.) who was adapted into older European figures like Sinterklaas, which resemble our current iteration, but the version we have now has no true original. It is a simulation without referent, and it’s a simulation that needs no referent. The referent is irrelevant.

Over time, culture begins to interact not with the arch-referent, but with the simulacra. My favorite example is one Baudrillard’s most well-known and controversial claims: that “the Gulf War did not take place,” a view he details in his book, The Gulf War Did Not Take Place.16 What he meant wasn’t that bombs didn’t drop and such, but that the version of the war people experienced and recollected existed only in the media.

Unless you were physically present, you didn’t experience the Gulf War as such, you experienced a simulation of it. Even the images you saw on television were curated, filtered, and reconstituted. The contrast, angles, edits, and broadcast contexts all shaped how you perceived it. Even on the technical level, what you saw was not the physical event, but a stream of reorganized visual data, the transmission process itself structures the representation (i.e. the image is shot through the air as disparate bits of information encoded onto a wave, then reformed on your TV set).

Of note: simulation was defined relatively early in Baudrillard’s career,17 and it’s not an outright forgery. Think of the postmodern act of “remix” here. You take bits and pieces of things and rearrange them into a new whole, telling a new story. In music, this act is generally well-received as authentic artistic expression, in news media, it’s generally frowned upon by everyone on Earth.

The cumulative effect of this simulated war is that most people didn’t experience the Gulf War as such wasn’t experienced, perceived, recalled, understood, or anything else we might associate with “the Real.” They experienced a version of the war that was prepackaged, and prepackaging wasn’t something Baudrillard loved. It was too tame, too manageable. It was finite and disenchanted for the sake of distribution (that’s right, Baudrillard laments disenchantment too).18

The implication, then, is that we respond to simulations as if they were reality. We build political opinions on them, shape identities around them, make decisions through them, perhaps decisions with dire consequences, if we’re in congress or something. The more we interact with simulations, the more we produce new simulations in response, until our social world is made up almost entirely of second-, third-, and fourth-order simulacra.

Baudrillard believed this meant we had become largely detached from the arch-referent, nature, and therefore, the Real.19 The cultural landscape was called, for many years, hyperreal, which is realer than real. You know, a super HD image of a leaf can be more detailed and beautiful than any leaf you’ll ever see in real life. That sort of thing.

Great example: I’d spent so long away from the woods of the Southern states that I forgot the experience. Nostalgia made me forget what coming here made me remember: it’s hot and full of ticks and snakes hiding in leaves and stuff. Awful.

Even our return to nature often takes place within the logic of simulation. People go into the wilderness, but how often is their experience mediated by their inclination toward digital presentation. They “capture” nature and redistribute it just like the media captured the war for distribution.

That’s the world Baudrillard describes; one in which meaning is no longer grounded in reference, but endlessly circulates in signs (images, codes, etc.). And it’s this that makes him such a complicated figure for metamodernism to integrate. Because while metamodernism is positioned as a transcendent, best-of-both-worlds via media between modernism/postmodernism, the manifestation of the “new sincerity” everyone’s been predicting for like 30 years. We’re not pre-critically naïve, we’re post-critically naïve by informed choice.

Baudrillard poopoos this sentiment.

He spent his life trying to think of ways subvert this hyperreal system. Early on, it’s Seduction. Later on, as he became more pessimistic, he offers some final possibilities in Fatal Strategies that might still disrupt it. He never fully lost hope, but, you know, mostly. He stopped talking about simulation theory because he thought he’d reached its logical end. He also was mostly pessimistic about possible subversion. He even moved beyond the name “Hyperreality” and onto “Integral Reality,” a reality in which everything has been completely subsumed into the system.

Why does that matter here? Because this is about as quintessentially postmodern a worldview as you can get. In fact, it’s hyperpostmodern. Yet paradoxically, Baudrillard’s also a sentimentalist. He has a clear premodern longing. He didn’t just seek a subversion of the hyperreal, but a return to premodern forms of exchange.20 He experienced the Welsh concept of hiraeth, but for the premodern world:

an awareness of the presence of absence, kindling a feeling in which pain and joy are braided too tightly to untangle

So, this man who yearned for the premodern, yet was also hyperpostmodern, should be basically irrelevant in a metamodern society that’s progressed toward an oscillation between general postmodern and modern sentiments, without willingness or desire to return to anything premodern, right?

Wrong! The media landscape he describes is more relevant since the advent of social media, not less. In fact, he’s growing in popularity as a sort of prophet of the Digital Age.21

The more you read him, the more accurate he seems, and the inverse is true as well, because you’ve got to acclimate to his terminology, which takes some time. If his theory is valid—and I think it is—then social media is just the next logical step in modernity’s teleological development.

In other words, we're still inside the same system. We haven’t escaped it. So the question is: does our sentiment change anything? Does our oscillation between modern and postmodern indicate any transcendence?

I’d argue that it doesn’t. In fact, just the opposite.

Just as Baudrillard and others were operating within the skeleton of Marxist and Freudian thought, even after hollowing the guts out, they were still within them, just as they were within modernity. Postmodernism functioned within the superstructure of modernity. And metamodernism is doing the same. It’s less a break from modernity (or the proposed postmodernity), and more a continuation taken to excess.22

Now, evidently, the creature we thought we’d killed by hollowing its guts out turned out to be a leviathan that’s still very much alive, and has begun eating its own tail like an Ouroboros. The system is sustained by ceaseless consumption of its own rear end which sustains production of its body.

Media producing more media, producing more media, producing more media, ad infinitum.

Can you imagine any major event now that wouldn't immediately be subsumed into the social media feed? Maybe some cataclysmic physical event like a massive solar flare that knocked out the internet wholly, but outside of that, everything is fair game for production/consumption.

That’s why I see metamodernism less as a break with postmodernism and more as an extension of it, and therefore of modernism. The oscillation between sincerity and irony isn’t new, as far as I can tell. It was already present in some postmodern thinkers, even if not always foregrounded.23 The core of metamodern sentiment today can be found in postmodern texts, interviews, and so on.

Now, this isn’t to say that all of the traits of metamodernism are, which is why it’s still compelling. But this one particular thing seems to be right in the center, and it’s tough for me to get past.

America, [ ] yeah.

Alright, one final critique. There seems to be a general assumption of political currents within the framework. That is, generally, that people want to escape capitalism, work toward equity, toward reversing climate change, toward democracy, egalitarianism, and so on. The pseudonymous Hanzi Freinacht captures this idea in The Listening Society, admitting that in Scandinavian countries, even conservative political movements have to at least pay some homage to general green progressive thought.

But that’s not how things have unfolded in the U.S., where cultural tension between “woke” and “anti-woke”—progressivism and conservatism—has remained dialectical. The liberal consensus isn't totalizing here; it’s contested at every stage, even though it seems at times (and indeed, for years) to have shifted in one direction, the pendulum is always swinging.

Now, this isn’t a central point to metamodernism, I admit that. But it seems to illuminate a potentially fatal flaw: if we don’t treat the U.S. as a central driver of global culture, we misunderstand postmodernism’s origins. Baudrillard and others were constantly analyzing American culture. America was the engine of capitalist spectacle, we’re the avant garde of all things consumeristic, from fast food to social media to movies.

What, am I meant to believe this has shifted somehow since 2000? I mean, I know across the pond everyone’s gotten fat too, but there’s no way we don’t beat them across the spread. We’re throwing McDonald’s wrappers into our empty Amazon packages with our left hand as we scroll through porn with our right and fart into the gaming chair that some influencer we watched for 4 hours yesterday recommended.

I admit that I’m biased as a red-blooded American.

But I think most postmodernists would agree that we’re still at the center of the system.

So when people talk about progressivism, or postmodern gender theories, or the environmental consensus, they’re often referring to values that emerged in American discourse, even when refined or formalized abroad.

So, when metamodern thought broadly seems to insufficiently account for this oscillating dynamic within American culture—this persistent tension between conflicting sentiments—it seems to miss out on a great emphasis in postmodern thought. And without that, any extension into metamodernism risks being built on an incomplete foundation.

Anyway, that’s it.

There was one article a few years ago arguing that “oscillation” was less accurate than a sort of consistent tension.

I think it was Zizek who claimed Marx was likely more teleological than Hegel. I can’t remember why he said this (if he said it), but I remember hearing it and going, “Ah, yes, yes.”

Yeah, social media is probably the new panopticon. Everyone says so.

Some Medievalist or whatever they’re called wrote a whole book on the things we blame Middle Ages for that aren’t really their doing.

I’ve said it before, but if you say, “ah, power is a metanarrative, postmodernism is incoherent” you’re not clever. That critique has been made 10,000,000 times. Foucault is explicitly concerned with power, Lyotard is the one who summarizes postmodernism as incredulity toward metanarratives, and most other postmodern thinkers are relatively specific in their critiques, rather than broadly being concerned with “power.” Heck, even Foucault was. His work is, in the abstract, broadly concerned with systems of power, but he accepted their inevitability, and took it to himself to critique specific systems. His cross-temporal and cross-cultural methodology tends toward the metanarrative, rather than the small narrative, so you should take it up with Lyotard, not Foucault or “postmodernism” broadly.

Baudrillard is probably the quintessential example of this sort of thing.

Who was okay with it? I don’t remember reading anyone who said, “Yeah, that’s me, he nailed it.” I’m sure it happened once or twice.

Gilles Deleuze called Baudrillard “the shame of the profession.”

I wouldn’t have to be so hedging in my statements if everyone in the world who knows 2 things about postmodernism wasn’t such a pedantic jerk about everything.

I originally had this as “if modernity is a religion, postmodernists are its blasphemers,” but I switched it up to manipulate you into viewing postmodernism with a slightly more favorable lens, since Elijah is the good guy in that story as it’s presented. This move of mine, a subtle shift in framing to elicit a subconscious response from you that fits my agenda—classic Hegemon move.

Cringe.

Deleuze and Guattari, I don’t know. I don’t like much of what they wrote, and because they co-authored Anti-Oedipus, I never speak of them separately. Full disclosure, I don’t know much about Kellner or Rorty.

For what I mean by “backcloth” here, see The Discarded Image.

I know I’ve called myself a card-carrying Taylorite elsewhere. I have a George Costanza wallet.

This was, I think, also in Utopia Deferred. Maybe in The Evil Demon of Images, but I don’t think so. I’m not checking.

I made that joke at a conference once and got some stifled chuckles, and I’ve squeezed it in everywhere possible since then.

Might be in For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign.

From memory, he refers to disenchantment explicitly (without reference to Weber, that I recall) in Symbolic Exchange and Death, in the interview portion of The Evil Demon of Images, and a few other places I can’t recall, but maybe even Simulacra and Simulation. It’s hinted at in all his work, to be fair.

Which was intermingled with illusion, so he’s using basically every word slightly differently than everyone else. Sorry.

Symbolic exchange, specifically. See Symbolic Exchange and Death.

He was praised for his representation of hypersexuality by Michael Knowles like 2 months ago. He’s in the mix, guys.

A very Marxist/post-Marxist way of thinking.

I’ll fully admit they were often sassy in debates and interviews.

Great read Michael! And the memes were very much appreciated 👍

Gonna have to read this one on my kindle.

My gripe is that while I know we need names and labels for things, the word "modern" actually means something, and "postmodernism" has always irked me for that reason alone.

As far as "meta," etymonline has some interesting info:

*"The third, modern, sense, "higher than, transcending, overarching, dealing with the most fundamental matters of," is due to misinterpretation of metaphysics (q.v.) as "science of that which transcends the physical." This has led to a prodigious erroneous extension in modern usage, with meta- affixed to the names of other sciences and disciplines, especially in the academic jargon of literary criticism: Metalanguage (1936) "a language which supplies terms for the analysis of an 'object' language;" metalinguistics (by 1949); metahistory (1957)"