The Death of Progress

Horizontal value systems in the Digital Age

The Myth of Progress

The idea that the past was ignorant and we’re less ignorant is nothing new, and I should think it requires little explanation. But I will clarify that I understand this isn’t ubiquitous—there’re plenty of folks out there who view the past (usually articulated as tradition) as carrying more wisdom, knowledge… Truthiness than the present. Despite this, I think it uncontroversial to suggest that “we know more than those guys” is the norm these days, and the opposite is generally understood as a subversion of that norm.

Here's an example: were the “Dark Ages” really so dark? Do a quick search and you’ll find plenty of historians saying, “plenty was happening, and we hate this term!” They’re saying, “Despite what you’ve been told, they weren’t dimwitted and uncultured!”

“Despite what you’ve been told” being the operative phrase here. They assume you’ve internalized the so-called “myth of progress.”

Myth here being used in the traditional, rather than pejorative sense that refers to a load of bologna. It’s a story, a guiding framework, it might emerge organically, it might be made up, but it’s of some social import. And ours is the story that we are advancing technologically, morally, socially. That, as a result of cumulative human knowledge, each generation is better off than the last in most ways.

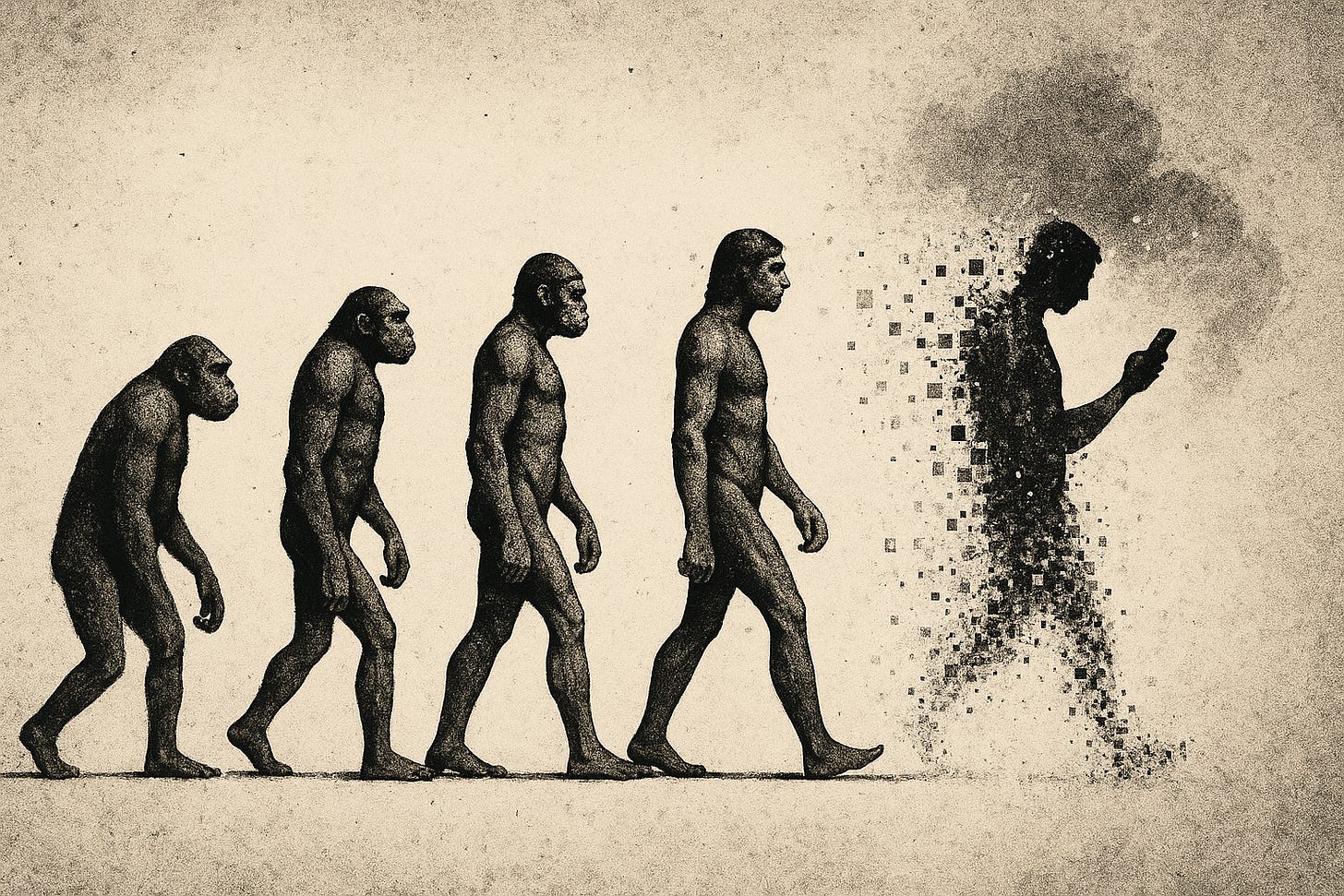

In some ways, that story holds up. Technology has undeniably advanced. In philosophy, there’s at least a structure—students still engage with past thinkers. If you study philosophy seriously, you trace ideas through time (often beginning with Socrates). That encourages continuity and development, absolutely. The Great Conversation is a building process, where thinkers read other thinkers and respond to those thinkers and are, in turn, eventually responded to. This perpetual dialectic seems destined to go up, up, up!

But what about the rest of us?

Or, more precisely: is the English-speaking world, or the West generally, “progressing”—hereafter used to refer to some broad intellectual development—at all?

Incoherent Accessibility

We live in a time of unprecedented access to information, and that access has come with fragmentation. Not innately, but likely as a result of at least few things: the sheer amount of information available, and our unwillingness to organize it. In The Discarded Image, C.S. Lewis describes Medieval thinkers as systematizers. They are taking the whole of the ancient world and categorizing, preserving, dismissing—you know, imbuing with value.

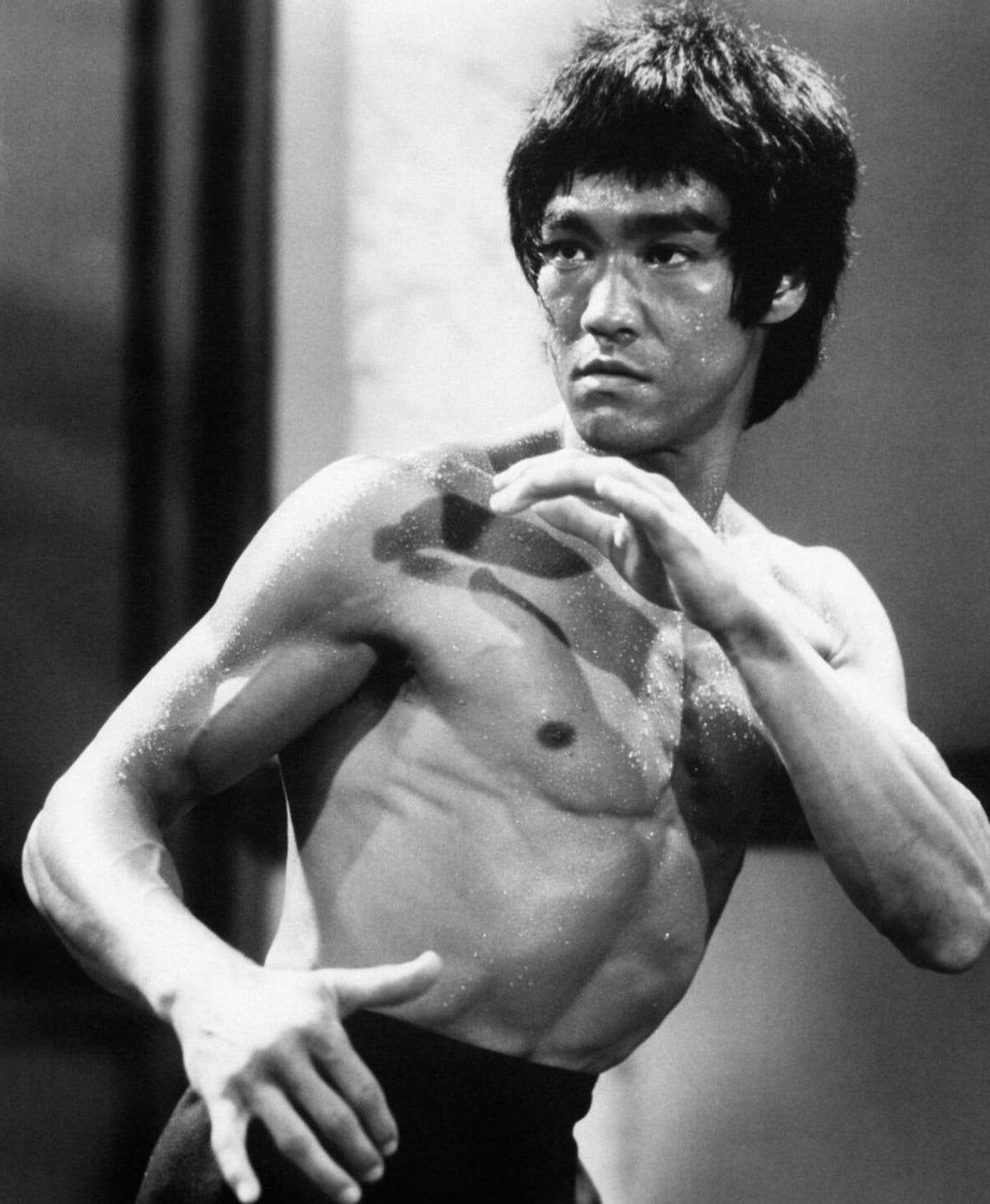

Now that we’ve got more information than ever before, it seems like it’s a great time for just this sort of project. It seems, unfortunately, that we’re not there yet. We engage the past and all its lessons in a piecemeal fashion. Here, I’m reminded of Bruce Lee’s philosophy of fighting—a philosophy that many an MMA fan has lauded:

“Absorb what is useful, discard what is useless and add what is specifically your own”

That’s good stuff! But unfortunately, it’s contingent on an understanding of what’s useful, which requires learning, experience, and real-time testing. Simply: if you’re not familiar with fighting, you haven’t got the know-how to discern what’s useful/useless, or what to add. Applied to social structures, this Tao-inspired approach would work well enough if we had the collective trait of discernment.

If our sentiments were not mere sentiments. If our eclecticism was not merely eclectic. But, in the absence of this sort of collective intuition, we run risk of treating history as a grab-bag, where the act of grabbing is conditioned by we know not what.

The Loss of Sequence

Even how we teach history reflects this piecemeal, highlight-reel, hardly systematic approach. I had a colleague whose Master’s (Education) thesis argued that American schools ought to teach history chronologically, and she made a compelling case.

The alternative, and I’m speaking from experience here, might have students learning World War II in 4th grade, the Crusades in 7th, and the Peloponnesian Wars never. This isn’t unusual. When you strip history of sequence, you strip it of context. And without context, nothing builds.

I used to tell my history students that if they just get a rough idea of the centuries that events occurred, they can go a long way before not knowing specific dates really harms them. With some knowledge of what impacted what, they’re able to build a sequence like:

Persian invasion unifies Greek city-states → Sparta leads land defense, Athens develops a navy → Themistocles expands Athenian navy → Athenian dominance grows → Delian league forms under Athens → Peloponnesian league is sick of Delian bologna (much of it taxation) → Peloponnesian War(s) → pan-Hellenic balance is weakened → Macedon rises under Philip II to take advantage of Greek city-state fragmentation → Philip hires Aristotle to tutor his son, Alexander → Alexander inherits insane military ambition and Greek philosophical formation → Alexander conquers most of the known world, including Persia

From that, students can say, “Hey, look at that, what goes around comes around!” Now that’s progression. It’s developmental, iterative, and even ends with an abstracted conclusion.

The Sciences Get It

Our most valued academic subjects still understand this. Think of physics—you start with some prerequisite math, you build your way up through basic principles, and then you tackle more advanced concepts. Each idea rests on what came before. You can’t do calculus without arithmetic. You can’t make sense of modern physics without classical mechanics.

Mathematics is obviously similar. If 10 by 10 stopped equaling 100, mathematicians would be in a real panic to figure out both why and what else is affected. By goodness, this isn’t conjecture, this is proof, man! If we can’t trust proof, we can’t trust anything… including any proof used to overturn our proof.

And, because mathematics is upstream of physics is upstream of chemistry is upstream of biology is upstream of social sciences, the implications would have to be unpacked across all the sciences. How many generations upon generations of work would this take to unravel?

Note: I barely skated through my undergraduate mathematics program, but I know proofs well enough to know this is a stupid, impossible example. Don’t attack me.

The quantum world complicates the broad picture that includes Newtonian physics, it doesn’t contradict it and condemn it to the trash bin. Indeed, and for good reason, the sciences (especially the hard sciences) are very wary of the trash bin.

But when it comes to culture, we’ve little fear of the trash bin.

The Enlightenment (Sorry)

Now, I despise being fashionable, and it’s become increasingly fashionable to—as the kids say— “throw shade” at the Enlightenment. I find a lot of Enlightenment philosophy to be tedious reading, sure, but that’s not to say that it’s not worthy of respect. That said, some (much) blame is rightfully laid on them for our current milieu.

This isn’t to say that the most notable thinkers of the era were poorly, sporadically, or non-developmentally educated. The rationalists, emerging from Cartesian tradition, are quite easily rooted in tradition—with empiricists certainly doing the same (science types will say something about Aristotle here, probably). Whether we think they’re in error or spot-on, Enlightenment thinkers are exploring the implications of the past as best they could. Doing, in the fashion of Bruce Lee, the hard work of absorbing, dismissing, and adding what was uniquely their own. Of course, the philosophical intuition to do this hard work was hard-won. Certainly, we wouldn’t claim that Hegel was historically illiterate or that Kant never read the great philosophers.

I’d be in good company if I argued that Locke, Kant, and Rousseau could be seen as trying to preserve coherence after religiosity began to wane. Long before Nietzsche declared that God is dead, the decline of religious authority in public discourse had been occurring.

Again, there’s a coherent system/sequence of thought here:

Reformation occurs, rise of merchants, monarchical system declines, New World discovered: mankind is capable of anything, even liberation from longstanding systems—up to and including nature.

Humanism rises in alignment with declining authority structures, and eventually the Enlightenment begins to explore what it really is that governs mankind.

Individual dignity is enshrined, transcendent moral order (natural law) is an explanatory principle for both the new era and the old, and we’ve got a scaffold for Modernity.

Part of the scaffold is, I’m sorry to say, a rise in secular thought.

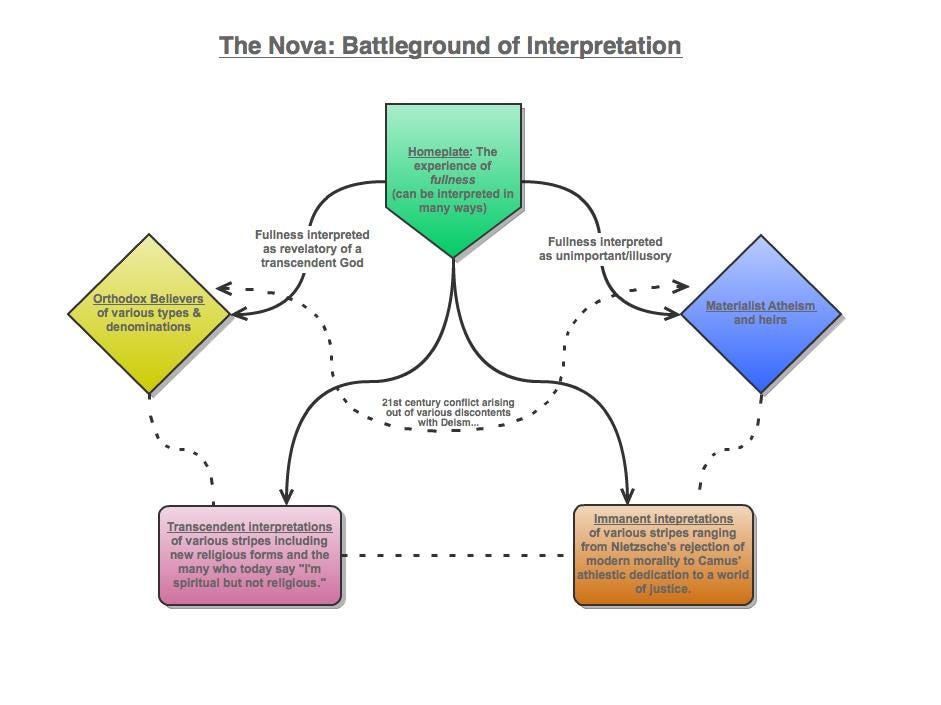

The Nova Effect & Le petit récit

Charles Taylor of A Secular Age fame1 would suggest that secularism isn’t just a decline of religious belief, but a rise of pluralism. This is a condition where belief is just one option among many, and none can claim uncontested dominance. He calls this the “Nova effect”:

“the positing of a viable humanist alternative [to Christianity], set in train a dynamic… spawning an ever-widening variety of moral/ spiritual options.”

Here, still, we’re not necessarily at the point of non-developmental thinking. In the same way that quantum physics complicates Newtonian physics by expanding the borders and adding context to the field, the Nova effect contains this “ever-widening variety” within a meta-category like “religion” or “schools of thought,” and that category can be dealt with however we please.

Now, this meta-categorization is probably an innate and inevitable thing that we humans just do. But there’s a focus issue that seems to occur. Jean-François Lyotard, in his seminal work The Postmodern Condition, describes postmodernism as “incredulity toward Grand Narratives”—that is, skepticism toward the overarching, totalizing frameworks (like progress, reason, emancipation) that once gave coherence to cultural development. In their place, he points to the rise of petits récits, or little narratives: localized, partial stories that resist universal claims. This isn’t quite the same as saying that all of history was only little narratives, but rather that grand ones no longer compel belief or legitimize institutions as they once did.

Taylor is obviously aware of, and indeed both discusses and references the postmodern thinkers2, but going forward, I’d like to emphasize, more than he would, the level to which we immerse ourselves into these little narratives.

To be clear, Western thought developed into the Nova Effect—this is still progress, even if we don’t love it. If we believe at all in the developmental nature of Western tradition, we ought to reject the idea that history has only ever been a series of disconnected, local accounts. My contention here is that we’ve internalized that idea (even though most of us haven’t read Lyotard), and we live according to what could be called the “myth of plurality.” Again, Taylor doesn’t go this far. He gestures toward a cross-pressured culture, but I’d argue most of us are already living Lyotard’s petits récits without even knowing it.

That is, if Western intellectual tradition was, with obvious fluctuations, aberrations, and so on, on a general trajectory upward (“upward” here refers to collective understanding of how the world works) the journey has lost its incline and become horizontal.

Society, Unmoored

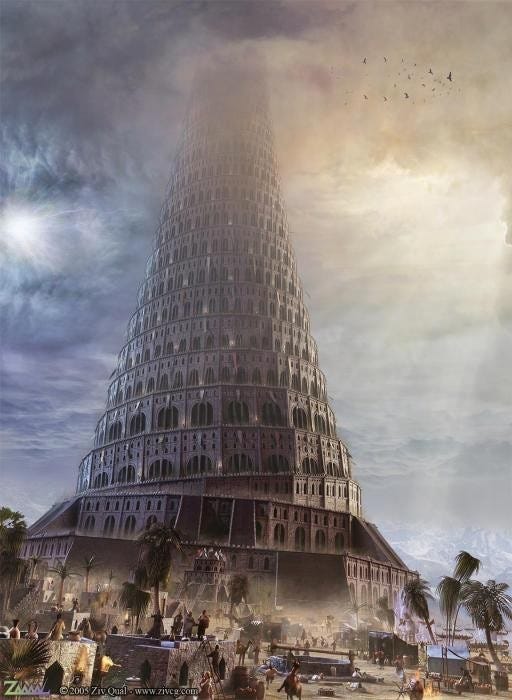

It’s as though we continued building the tower of Babel until we breached the atmosphere, and then kept building. By Jove, we’ve progressed into the heavens! Now, we’re past Earth’s gravitational pull. Then we ran out of materials, so we started grabbing bricks from the tower beneath us—without fear, mind you, because we’re in space without risk of falling. Now, we’ve got a boatload of materials free-floating around us, but no grounded footing and no means to descend safely back to the ground. We’re adrift in space, doomed to arrange and rearrange the bits and pieces we’ve salvaged into makeshift platforms just to feel like we can stand on something.

It's not just being unmoored3 that’s got us latching onto petty narratives, there’s also some intentionality behind it. Social media is a (the) major part of our culture, it runs on engagement, engagement favors extreme emotions, extreme negativity beats extreme positivity, so we’re constantly, powerfully compelled to go all in on extremely engaging, usually negative, small narratives. Elon Musk is at war with Trump! Not too long ago the war we were all so concerned with was the war in Ukraine. For a few months a few years ago, it was fear of a war with North Korea.

The terrifying intentionality that drives media and social media find a captive audience in the unmoored West.

The rapid investment and exchange of these little narratives leads, inevitably, to abstraction.

Remember how investigating hundreds of years of Greek history led students to the proverb, “what goes around comes around”? That’s how a developmental abstraction might occur. There are plenty of other lessons to abstract from that historical period, some erroneous, some profound, but they take time and diligence to discern, and when they’re discerned, there’s a density to them. They’re weighty, as they’ve been used, hopefully, to summarize generations—possibly thousands of lives.

That sounds great and all, but why bother with that process? Someone took the time to summarize those things for us on Wikipedia, and we can read the first paragraph of Wikipedia, get the gist, then add what is specifically our own. We’ll toss that out into the world in some algorithmically digestible format (negative, extreme), and see what people who’ve maybe read Wikipedia, but probably not, have got to say. If they like it, we’ve got ourselves a lesson.

A proverb that was stupid would find enough of a local audience to stick with a few, but would die off soon enough. A proverb that was only useful in a specific region like, “don’t go outside in a monsoon” would never make it out of that region. For something to merit preservation across hundreds or thousands of years and multiple regions, it would have to be pretty good. Then, and only then, would tens or hundreds of millions of people be exposed to it.4

There are Twitch streamers who can hit those numbers in a day.

We can simulate the developmental process of abstraction so well and so frequently that we fill our minds to the brim with poorly thought-out aphorisms and never have it occur to us that there’re well-thought-out aphorisms just lying in wait for us in our traditions.

But then, even if we found them, we’d pluck them out and recontextualize them. We drain them of context and fill them with our beliefs, then, rather arbitrarily, aggrandize them. Look what we’ve done with stoicism.

We’ve little inclination to organize stoicism within a system of beliefs because, despite a “system” here only referring to an understanding of how things relate to one another, systems scare and upset us. “The System” is what’s gotten us into this mess!

That sentiment is another petit narrative—revolution and resistance, truth to power, whatever.

To return to the space analogy: if we’re adrift and building free-floating, makeshift platforms to stand on as we drift, we’ve also tethered ourselves to one another so we’re all drifting together tangled up with ropes. Occasionally, that we know not what that I mentioned has conditioned our temperaments will become a we know what and the what turns out to be “the System” or something like it. The System is what allows for some jerk pulling on the ropes to drag the rest of us toward them. And if/when one person finally falls out of orbit, it’s the reason the rest of us will be dragged down and crash into the ground.

But at least we’ve transcended those troublesome systems way down there on the ground.

For the Enlightenment philosopher G.W.F. Hegel, as society progresses, there are aufheben—a word which carries, simultaneously, the ideas of uplifting, abolishing, and preservation. Alexander the Great uplifted Greece by transcending the city-state disunity and forming a unified empire. He also abolished Greece or cancelled what it was by conquering it, obviously. However, in his global exportation of Hellas, he preserved Greece forever, even after the Macedonian Empire fractured.

These days… well, we’re pretty good at the “abolishing” part.

An Emergent Ethic

It may seem fatalistic or extreme to describe society as a free-for-all of values, but why? One of the largest and most influential YouTubers in the culture/game space is Charles White, also known as MoistCr1TiKaL or Penguinz0. He’s entertaining enough, and often reacts to cultural events like some famous person saying something odd, or some YouTube beef. When he does so, he makes emphatic statements like, “this guy’s a total goober.”

We all know “goober” is a negative term, but often the ones described so uncharitably would be, in most societies across history, pretty normal. Maybe it’s a guy who was harassed and shamed publicly decided to threaten violence. That’s a big no-no, because our sort-of-stoicism combined with our collective agreement that all such threats made remotely are performative, and so the only honorable response is to shrug it off and care less. In fact, even if a society that advocated pacifism (wouldn’t be a society, but a subculture) would say the person is in moral error, but wouldn’t mock them as a goober or anything similar. The sentiment to react with violent intent against dishonor is just about as old and cross-cultural as anything, but in the last 20 years we’ve decided it’s cringey (we avoid “wrong” in such petty cases, because we know that performance is so deeply embedded that people will embrace their wrongdoing).

This is not anomalous or unique to Charles, rather, he’s exemplary. He captures and channels the moral intuitions of the online public and codifies them, of course adding what is specifically his at the same time. This is not to suggest that the role he and those like him play is innately problematic; there’s a demand for it, but those things he codifies emerge from a culture so fast-moving that it’s barely understood what it was reacting to by the time it’s reacted.

Across many influencers and many millions of interactions, we see the real-time emergence of ethos in the new West. What societies had previously entrusted to those who’d internalized the Great Conversation, we now crowdsource to those who’ve internalized the little conversations.

Conclusion

I’m obviously biased in my characterization here. As a Catholic, I’ll always appreciate the idea that values be grounded in tradition or at least exist in some relation to it besides “not that one.” So, it’s no surprise that I’m a bit prejudiced against what we call progressivism these days.

That aside, it seems like a category error to even describe what we’ve got going on as progress of any sort. Not simply because it’s an erroneous development, we’ve had plenty of those—Marx is an organic, (I think) erroneous development of Hegel, who was himself an organic development of the early Modern era. What we’ve got now is no development of any sort. It’s a new thing altogether.

The Nova Effect made space for the myth of progress to be subsumed into the myth of plurality. This oughtn’t be viewed as a replacement so much as a zooming out. We zoomed out enough to see that the myth of progress was one myth among many, transforming it from a single upward arrow into a constellation of little lights. A whole mess of powerfully engaging little narratives that we hop in, abstract lessons from, and then apply those lessons as we hop from narrative to narrative, until they’ve worn their welcome and are dropped.

It’s not that we couldn’t trace the causal relationship between some little narrative and some Grand Narrative, it’s that we don’t care to.

That’s not fair. He was still pretty famous prior to his magnum opus… but I didn’t have to learn about anything else he wrote when I was in grad school and neither did you, so I’m saying this is what he was famous for.

He even cites Foucault’s Discipline and Punish—read his footnotes next time you’re making blanket statements poopooing postmodern thinkers!

Taylor called this a disembedding. I’ve also called it an untethering elsewhere. You get the idea. Lewis considered it a deviation from the Tao, but since I’ve already referenced Taoism here in a more precise context, I figured that’d be confusing.

It’s in vogue these days to discuss how systems of power are the primary means of preservation of all such proverbs that have, in any way, become embedded in powerful civilizations. This is reductionistic. The amount of extraordinarily powerful people who we don’t have records of should stand as a testimony against this.

Loved it. Great read. I thought I detected a bit of Ecclesiastes in there, which reminded me of a similar take I had written the other day:

https://dotmilk.substack.com/p/under-the-same-sun

Great stuff man! Thanks for sharing.