Lady's Domestication of the Tramp

Lady and the Tramp is currently one of the 6 or 7 movies that’s been on repeat in my home over the last couple of months, and although I never really cared for it when I was young, getting to see it through the eyes of children helps make it seem a little bit more special. That, and it’s often a reprieve from the incessant Finding Nemo cycle we so often find ourselves caught in around here.

The aim of this article is to step back from the heavier cultural stuff I’ve been dealing in, and do something a bit more fun. That is, reflecting on pop-culture stuff in a not-very-robust, not-at-all-formal, not-very-well-researched sort of way.

Meeting Lady

The movie starts out with this wonderful little introduction of the dog, Lady, in a sort of, you know, collar-and-cufflink, prim & proper sort of home. It sets her up as a hifalutin protagonist, and foil to the lofalutinTM protagonist (the Tramp) of the movie.

She starts out as a puppy, and then you see that her owners—who she calls “Jim Dear” and “Darling”—are trying to train her. She’s barking because they’ve left her in the kitchen. And Jim Dear’s like, hey, you’ve got to discipline her right out of the gate. But Lady persists, and busts on out of the kitchen carrying on. She’s reprimanded and placed back. But she persists, and he says, “All right, just for this one night.” Well, wouldn’t you know it, fast forward—she’s already an adult and still laying at the foot of the bed.

So, who’s Lady? Well, I hesitate to use the word spoiled, because that has such a pejorative sense to it. Privilege would be more technically accurate, but again, still pretty culturally loaded, and I’m hesitant to sweep Lady into our modern cultural stupidity. Suffice it to say, she’s well cared for and not wanting for much.

Then comes the catastrophe: Darling gets pregnant. And due to the stress of the situation, Lady’s usual antics—as a very normal, well-loved dog—aren’t quite as well received. She gets slapped by Jim Dear (this is back in the day, when slapping a dog was “normal” to “a little harsh,” not a hanging offense). Lady’s recounting the events it with her friends—these two other neighborhood dogs who’re a lot of fun—and they try to reassure her.

“Babies,” they basically say, “are real special, they’re real swell, but yeah, things are going to change.”

Meeting the Tramp

Now, the Tramp is from the complete opposite side of dog life from Lady. We’re introduced to him on the street, and he’s presented as a street-savvy kind of guy. He goes around town, gets breakfast where he wants because he has good relationships with a couple of restaurant owners. He’s got access, he’s got game, he knows the angles, the ins and outs of being, as it were, unleashed. At that time, there’s a dog-catching ordinance in effect: any dog without a license is going to be rounded up. And sure enough, two of the Tramp’s friends get caught. He frees them from the pound, tells them to run, and he ends up fleeing into a fancy neighborhood.

A fancy neighborhood that just so happens to be Lady’s fancy neighborhood.

The Tramp overhears the conversation about the baby and invites himself into the scene. He’s trespassing, so the other dogs are like, “Hey, who the heck are you?” But Tramp largely ignores them, and weighs in on the catastrophe, basically saying, “Oh boy, everything’s about to change for you.”

Babies are the end of a dog’s life as they know it, in his view. He says, “You won’t be able to bark like you used to. You’ll try to come in wagging your tail and they’ll tell you to get lost. Your love and attention are about to be redirected.”

And these are not inaccurate observations. Big dog lovers almost necessarily have to scale it back a bit when there’s a baby in the house. Babies are vulnerable and they’re more important.

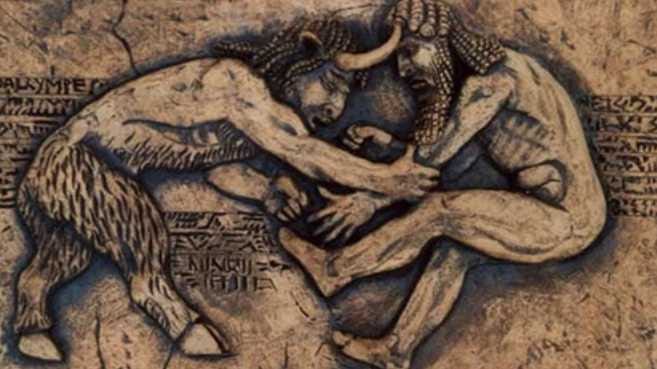

Gilgamesh and Enkidu at Uruk

This is the introduction of a tale literally as old as tales themselves: the wild versus the civilized. If you zoom out, you’ve got chaos and order, yin and yang, all that stuff. But more specifically, and what most literature nerds would focus on: primal vs civilizational, wild vs. civilized, nature vs. culture, maybe even man vs. nature, if you watch it cross-eyed or something.

Probably the oldest story we’ve got is The Epic of Gilgamesh. In it, you’ve got the tyrant king Gilgamesh, who’s a real piece of work—oppressing his people, sleeping with everybody’s wife. The people cry out to the gods: “Somebody’s got to stop this guy!” (paraphrased) So, the gods send a counterforce; a wild man: Enkidu.

He lives with the animals, eats grass, runs around all free and quick. He’s the wild man. He’s an animal, more or less. And he’s strong—strong enough to match Gilgamesh, who’s part divine, for Pete’s sake. But how do you civilize him? How do you get him to take on the fight against Gilgamesh? How do you get him to stop giving a hoot about the deer and start giving a hoot about human life?

And the answer is feminine, and it’s civilizational. They send a priestess to sleep with him (let’s not get into a whole thing about priestesses sleeping with people, it’s a whole Ancient Near Eastern can of worms). After that, his legs are weak. The animals run away from him. He can’t keep up anymore, and he’s become something altogether different. That’s what it took to domesticate the man: a woman. And now, he starts to see things from the domesticated perspective. He says, “Okay, I get it now,” and confronts Gilgamesh.

They fight. They have this huge wrestling match—I won’t spoil who wins. I won’t even speculate what kind of throw it was.1

Civilization versus wildness occurred with the priestess, and then again with the wrestling match… then they go on this awesome adventure where it’s basically two tough guys whooping everyone and making gods mad, and I won’t spoil the rest.

Now, interestingly, in some (you know, Jungian) systems of interpretation, the chaotic, primordial, wild thing is often associated with the feminine. Take the Mesopotamian creation myth (Peterson loves this one): Tiamat and Apsu. Saltwater and freshwater mingle, and from that co-mingling, the gods are born.

The Civilizing Feminine

But in Lady and the Tramp, as in Gilgamesh, it’s the civilizing feminine. Lady is the domestic center, Tramp is the wild man. So, they interact a bit, the Tramp leaves, and the narrative progresses: the aunt shows up, and those Siamese cats wreak havoc. They’re conniving little jerks. They go after the fish, knock stuff over, destroy the place. And Lady gets blamed. So, the aunt muzzles her.

That’s one step too far. She bolts, quickly running into the Tramp again. Now you’ve got the Aladdin trope: streetwise guy takes the princess on a tour of the unsheltered world. “Let me show you what’s outside those walls.”

They go on adventures. He helps her get the muzzle off. They eat spaghetti.

It’s charming. He shows her his world. He’s like, “We don’t need those humans. We’ve got this.” But then she says, “Who’s going to take care of the baby?” And boom. That’s the moment. That’s the pivot that’ll tame the wildest of wildmen if they’ve got any huevos at all: family, duty. That’s the thing that pierces his romanticism of the wild. It got Vegeta in Dragonball Z, it would’ve gotten Jack in Titanic, and there’re countless others.

The Tramp concedes, saying, “I’ll take you home.” The seed of civilization that was planted the moment he laid eyes on Lady begun to really take root at that point.

Eventually, another catastrophe arises: Lady gets caught by a dog catcher and thrown in the pound. There, she meets some of his associates, including an ex-girlfriend who gives her the whole scoop on this Tramp. Turns out he’s a bit of a player.

Now, this part is important: he is sincere about Lady, but she questions it. He’s not running a game this time, but he’s still got the baggage associated with him. So, the question is: can he be redeemed? Can the wildman become something else?

Catastrophe, Eucatastrophe

The answer the movie gives us is yes, but it’ll take some action… even some self-sacrificial action.

And that action comes when he sees a rat sneaking into the baby’s crib. Now, recall, at this point in the story, the Tramp is on the outs with Lady. He’s a dejected lover, and a wildman, so he’s got that unpredictability to him. It’s a classic misunderstanding: he freaks out on the rat. He chases it down and kills it. But the aunt sees this chaos and assumes he’s attacking the baby. On seeing the aftermath, initially, even Lady thinks the same. The dog catchers take him into custody.

But, Lady investigates the room. She barks, shows the humans the truth—look! The rat! He was saving the baby, not attacking him. So, the truth comes out, a rescue mission ensues, and he’s freed.

But, what’s the new freedom? Is he back in the wild again? Nay, friend, he’s brought home—Lady’s home. He’s adopted and collared both literally and metaphorically, as he commits to Lady and has puppies with her. He’s part of the family now.

This is the lesson we’re offered from Lady and the Tramp, and it’s a lesson we’ve oft-inverted in our culture: that civilizing folk, bringing them into “polite society,” domesticating them, is of value. Disney explored both this trope and its opposite on the approach to the millennium, with movies like Aladdin and Tarzan, but that’s a discussion for another day.

Very often, Hollywood’s lessons post-millennium are to be more wild, be more free, be more crazy. Think of Along Came Polly, Forgetting Sarah Marshall, and every other romantic comedy.

But Lady and the Tramp, like Aladdin, like Gilgamesh, like Rocky, tells an older tale. The man must be tamed. The free spirit must be brought into order, and that’s a good thing.

I mean, this even shows up in ancient Greek art. They, for example, wouldn’t sculpt you with a big ol’ kielbasa as a compliment, that would’ve been mockery. It would’ve meant you weren’t in control of your passions. Our society has flipped it, and we celebrate that loss of control, submission to the passions (oh we wouldn’t admit to it if it were phrased as such, but that’s what it is).

Now, in fairness to the culture, this isn’t without reason. The turn of the millennium was replete with examples of, and beliefs that, the advancement of corporate stoogery and rigidity was turning men into subhuman cogs. This is, basically, the great struggle of Fight Club. The belief was that something primal was lost, and men had been domesticated to the point of castration.

So, these days, man-o-spheric endeavors often veer toward non-domestication as a reflex. Think here of “primal” movements and such. The assumed wildness of man that needed to be tamed now seems to be an assumed domestication that needs to be liberated.

You see this now in the new masculinity movement: 50-year-olds still trying to sleep with 22-year-olds. This DiCaprioery is, obviously, nothing new. But what is new is broad social support for men making it into the latter half of their lives untethered, and still thinking without using the head on their shoulders.

Cicero wrote about this in On Old Age. He believed folks were supposed to outgrow these passions, and replace them with other passions, like learning. You’re supposed to choose the life of order and duty earlier in life, cultivate the appropriate virtues, and then you’d be honorable (and, hopefully, treated with honor) in old age.

Tramp does exactly that. He puts on the collar and finds redemption, rather than shame.

An Anecdote

I remember during a stint in Baltimore, I was playing foosball with a friend’s kid, maybe 6 years old. The kid didn’t want to play fair, and, you know, fair enough. He’s a little kid, so some handicap seemed appropriate.

At first, he says, “You can’t block.”

Okay.

Then he says, “You can’t use the middle guys.”

Fine.

Then: “You can’t hit at all.” At which point I said, “Buddy, we’re not even playing foosball anymore.”

He thought getting rid of the rules would be fun, but it wasn’t—not for me, not for him. There was no game left, no joy to be had, no honor in victory, nothing.

Throwing off the yoke of restrictive social norms seems like a liberation, and in a way it is. But you may just find that you’ve liberated yourself from meaningful relationships in the process. The sort of relationships that make life worth living.

The unchained are anomos, free from yokes imposed from on high and free to participate in the yokes they see fit. They’re willfully participating in the ego-drama: “My rules. My outcomes. My meaning.” Which is great for a while, but not forever.

Lady and the Tramp teaches that domestication, order, rules, willful submission to others, these are good things. Yes, yes, it was important for Lady to see that the world was bigger than her backyard. But the narrative’s telos was a bit of that and a bunch of the domestication of the Tramp.

His warning that babies ruin everything for dogs was partially right, sure. But only in the short term; in the ego-dramatic2 role he’d given himself. In the long term, babies complicate things for dogs, they dislodge the dogs from their role as child stand-ins and reorient them into a role of diminished attention, but (at least in this case) of greater fulfillment. Turns out, they weren’t ever meant to be child stand-ins… they were meant to be dogs.3

In the end, we’re given a dialectical resolution. Not simply that the wildman was right or the civilized feminine was right. But that the wildman was drawn into civilized feminine’s domain, and in that process, they both grew, comingled, and a new thing—namely, their family, and their properly fulfilling roles—emerged.

Lady learns that she’s not the baby anymore, that she’s not the center of attention. The Tramp learns that total liberty isn’t fulfilling. And none of this had to be explicit. These lessons simply emerged, they were baked in.

Some of this is likely intentional, but some of it is almost certainly an emergent product of the writer’s cultural conditioning. What that cultural conditioning is and what it means is a debate that can be traced to many schools of thought: Marxist-Gramscian, Freudian, Jungian. Perhaps it’s deeper than even depth psychology, and we’ve got our hands on Semina Verbi (or Logos Spermatikos, or Seeds of the Word).

Maybe it’s a bit of each.

Anyway, that’s Lady and the Tramp.

I’m going to write an article about this one day. I think everyone’s dead wrong.

Balthasar

And probably have families, so I’d be curious to hear about the ethics of spaying and neutering one day.

And this. Yes, this is movie three in our house. My daughter's first obsession is the original Little Mermaid, followed by Alice in Wonderland. Lady and the Tramp is what we turn to for some sanity between those two.

The Beowulf and Enkidu reference brought me way back. I forgot they used a woman to 'tame' him. What a great comparison for Lady and the Tramp!

This is such an excellent analysis! It's beautifully masculine to be drawn outside of oneself, and that's often presented in modern narratives as a "throwing off of the societal norms," as you say, but that individualistic focus can so easily end up in egoism. What it really means to be drawn outside of oneself is to be drawn into a life for the sake of the other. Bravo, I loved this piece!