Charlie Kirk's assassination was different.

Maybe it will bring about a turning point, after all.

Charlie Kirk was assassinated.

When this sort of thing happens, it’s fashionable to play aloof and say, “Look, we’ll all move past it within a week or two.” That’s part of why I kept editing this for about 2 weeks—I wanted to see if this claim was right.

Fortunately, for once, it wasn’t.

From the start, this one felt qualitatively different from the threats, events, and other acts of violence we’ve been seeing lately. I wasn’t exactly sure why, but as I spoke with others and listened to/read commentary, I noticed that this was a common sentiment.

It was no surprise to see that immediately after this event, a lot of people on the Right, especially the far-right, would say, “That’s it. We’re done. We’re gonna do something drastic! That’s the sort of thing people say all the time.1

It’s not even surprising to me that some people on the Right who tend to be more moderate, or part of the mainstream Right, would tend in that direction.

What was surprising were the responses of people on the (as Ben Shapiro described them) “Bluesky Left.” These unwashed masses are to be contrasted with the mainstream—the politicians, the news media, and so on. For the most part we can point to the Matthew Dowd types and think, they gave an ugly statement, but about what I’d expect.

In fact, my expectation was for a great many Dowdian sentiments to the effect of: Hey, Charlie Kirk was a very controversial guy. You can’t get away with this stuff forever, and so on.

Then, I expected the fringes—the nerds skulking around r/ANTIFA or something—to celebrate. However, I was shocked to find out, as many others were, just how common it actually was for these Bluesky Leftists, these “boots-on-the-ground” folks of the Progressive movement, to be openly posting disgusting things; spreading memes, pictures of themselves laughing, smiling, you name it.

It wasn’t just me who noticed, either. Again, a lot of people were saying, “People I know personally who are totally normal most of the time are saying all these things!”

It, evidently, became very fashionable to be flippant and joyful about this execution.

So, when folks saw Leftist officials’ responses condemning this as bad, many couldn’t help but feel that, as others have said, that they were out of touch with their constituents.

Note: the responses have more or less leveled out—much more common now is the non-celebratory, “he was a really bad guy so I don’t feel bad but I guess murder is wrong” sentiment on the Left, and the “he’s a martyr and we’ll come back stronger than ever” sentiment on the Right.

Some opinions on why it felt different.

Probably the most common sentiment is that this feels different because of what Kirk stood for, which is open dialogue. Theo Von said it’s hitting different, despite all the violence he’s seen, as well as his disagreements with Kirk on various topics, because of the respect he had for Kirk’s courage.

Many in comment sections have said something like: “Why am I crying for someone I’ve never met?” In response to this, one gentleman, Chad Prather, quoted by

said, more or less, “It’s not about proximity, it’s about meaning.”All these sentiments ring true, so I am really only adding to an already sufficient stockpile, but hopefully it’s useful.

The Atmospheric Conditions

There are broad cultural trends that give us a great deal of background on both sides and help to contextualize the event. These are the neutral, both-sides-applicable (i.e. metapolitical) “atmospheric conditions” that lie above and outside our interactions, and therefore Kirk’s murder. This isn’t comprehensive and it’s in no particular order.

The first thing I’ve noted is a unique ability (and I’m probably drawing this largely from metamodern literature) to oscillate between the universal and the particular. We might generalize our enemy (the Left or the Right, the far Right) and particularize ourselves. And we might do the reverse.

When it suits us, we think in collectives, and might even apply this thinking to ourselves. When there is an isolated person—for example, the shooter—we might say, “That person was a lone gunman and a nut job, not representative of us… and there’s really no ‘us’ and ‘us’ vs. ‘them’ thinking is bad.” We see this all the time with noncentralized groups that commit violent acts. But with the opposing side, it’s easy to point to them and say “they.”

A critique that was popular during the postmodern movement’s growth, and was adopted explicitly by the Left. Despite this adoption, both Left and Right have no issue engaging in the dehumanization of the Other. This was, in its beginnings, largely a critique of the economic bourgeois, but as we moved forward, we got guys like Levinas and Lacan to apply it culturally to not just the bourgeois or the petit-bourgeois, but to any who aren’t part of the cultural establishment. Now, it reaches its fullness in our wholesale demonization of political opponents, and all too often, both sides do this. Basically, the opposing political party is represented as some sort of existential threat.

Thirdly, stochastic violence—a more academic term—but something internalized in a profane form in the popular crowd: the idea that people could speak through coded or veiled language to convey a message meant to call others to violence. Now, we don’t like its application in the popular crowd, but on its face, this is obviously true. Anybody who’s ever seen a mafia movie understands you can use veiled or indirect language to give an order that leads to somebody’s death. However, the popular world, this has been, like everything else, broadened to apply to anybody who says anything “problematic.”

We can blame Leftist professors for popularizing this, but all too often, when the Right engages in whataboutism, they’re not unlikely to channel this stuff.

Next is distance. And I mean in a culturally permeating way. Media culture fits the name “media” in the sense that media is something that mediates—it’s in the middle of a thing. We have all sorts of things which mediate our experience. For example, people experience something and feel they have to take a photo of it—the phone/photo are mediators between the person and the experience.

We see this with the rise of drone warfare, I remember working as a contractor after I was out of the Air Force, and when they would play drone footage, we’d all get excited. These were live people getting blown up, and it was something like a video game or TV show. It didn’t really bug us. We knew it was live, we knew it was real, we knew those people really died. Were it in person, we might cheer and whoop, but you might afterward go, “That’s crazy, what we just saw.” But with drones, I saw and heard nobody expressed being fazed in the slightest.

So, things are increasingly distant, and distance blurs moral weight. Things don’t need to have as much gravity when you’re far enough away from them, and obviously we can see how this plays out on anything having to do with a screen, anonymity, any of the things associated with the internet and social media.

There’s also been a shift in discourse itself. We started to see, and this is something Ben Shapiro acknowledged multiple times over the years, that debate is context specific in purpose: sometimes it’s about getting at the truth with someone you can budge, other times it’s just to show the audience that you’re right. Over time, this seemed to develop into debate being (often) more about getting the clips and (as the kids say) “dunking” on your opponents than it was about discourse.

This isn’t to say that appeals to the pathos of the crowd are new, far from it, but the fact that this became the preferred form of debate (as opposed to, say, the “boring” exchange between Jordan Peterson and Sam Harris the first time they debated truth for two hours).

Here’s a term I’m borrowing from Maalvika: compression culture, our incessant need for summaries. This may well be the most problematic thing on this list. We need brevity, and we need it digestible and determinate. Thus, we need summaries, and we need them quick, quick, quick. So when we engage a subject, we want to know: hey, what’s the first paragraph of Wikipedia say about it? Easy.2

The next thing is negative emotion dominating positive emotion. Everybody knows this. Social media rewards engagement, which is associated with high emotion, and negative emotion almost always trumps positive emotion. If you can get people mad, it goes a lot further, engagement-wise, than making people smile.

Another thing people likely haven’t consciously accepted but have intuited is the democratization of power. We still point at heads of institutions (government, education, whatever) and problematize them, but we also know that if we shine the all-seeing-eye of Internet on them, no individual is beyond the power of its gaze; and we can do so rapidly.

You may say, “the Left sure tried against Trump, and he’s president again,” yes, for sure, but he had to galvanize >50% of the population, and still got a ton of lawsuits and a bullet through the ear.

The final thing, the meta-category that contextualizes all of these: the digital public square. The Internet is the new public square—every social theorist has written about this, it’s not new.

These atmospheric conditions lead to a sort of perpetual minor anxiety, big emotional waves of attachment to micro-narratives.

Violence on the Mind

Only a few months ago, we saw the execution of Democratic legislator Melissa Hortman and her husband in their home by a despicable monster dressed like a cop in a mask.3

Then, we had just seen one of the more gut-wrenching mass shootings in a while: the transgender shooter who shot the Catholic school where kids were praying in the chapel, opening fire and engraving things on the bullets.

Then, very recently there was a news cycle surrounding a stabbing in North Carolina of a Ukrainian immigrant, Iryna Zarutska. This took the nation by storm, in part because there was a belief the media had suppressed it, in part because it seemed politically motivated, but mostly because it was so disturbing.

Note: it seems speculative to think the stabbing itself was politically motivated—some have said that he mentioned her skin color afterward. But that could easily be a cultural distinction—i.e., she’s the only white girl on the train, so he said it because that’s her most distinct feature, not because he killed her to strike against the

We know it was disturbing because it was caught on video, and we could see just how unprovoked it was. Then, we saw her receive no help at all from other passengers. It was so unjust and disturbing in so many ways that many had a justifiably strong response to it.

Just as people were starting to put out their columns and do their podcasts, talking about what needs to happen, talking about how stupid cashless bail is (it is), talking about this despicable killing from this dork with his stupid long hair, and all those cowards who sat on the train—there was high emotional volatility.

So, just before Charlie went to Utah Valley University, everyone had violence on the mind. But, from whence would the violence come? Here, we return to the “storm winds” analogy; namely, the storm winds of Left and Right, which have overtaken American discourse.

The Left and Right

Is all this violence just in our heads? Well no, it seems like we’re indeed living in a time of civil unrest:

Through the first half of 2025, the US saw some 150 politically motivated attacks, said Michael Jensen, a University of Maryland researcher who tracks terrorism incidents. That’s nearly twice as many as the same period last year – a spike he said reflects growing discontent with the political system and its policies.

“What we’re witnessing right now is not the product of a single group or ideology but perhaps evidence of growing widespread civil unrest,” Jensen said Thursday.

Of note, the data don’t seem to indicate that the Left is behind most violent political attacks. Though some articles point out that the Right is behind most deaths, they avoid other ways of slicing it up, like “how many attacks” and such. One large study indicates that it wasn’t a Left/Right thing at all; rather, the key thing is that populism leads to more political violence, which, frankly, isn’t that shocking.

The Left/Right divide is extraordinarily intense, both feeling that they’re suffering from existential crises. Anecdotally, I’ve noted an uptick in eschatological (or existentially nihilistic) language being used by our youth. Think of “the world is burning” (especially as it’s used in memes) or “this generation is cooked.” They transmit the messages in annoying internet vernacular, but the comment sentiment is: it sure feels like things are going downhill.

Note: yes, every generation has thought this sort of thing. No, that’s not a compelling reason to think it’s not important.

On the Right, there’s fear the Left’s trying to turn the kids gay or trans or whatever and we need to shut down the education system; the whole progressive movement is trying to upend Western norms, all that.

On the Left, almost every subgroup is expressed as being at risk of the worst possible outcome: “They want to genocide the trans people; they want to genocide the Black people; they want to genocide the immigrants.” If someone actually believed that (I didn’t think they did until Kirk), they’d be sitting here thinking, “By Jove, I’m likely to die when I walk out of the door tomorrow!”

Behind every door a fascist might be hiding.

Or so we’ve been led to believe by the perpetual spinning of the yarn: “This is just how the Nazi Party rose to power!”

Note: there are parallels, to be sure, but all too many differences; moreover the general strategy behind the parallels isn’t close to unique to Trump… again, the threat of some ontological Other being placed in front of the population is a bipartisan thing.

The Left has been so keen on calling the Right, not just bad guys, but really really bad guys, and that no small amount of folks on the Right (particularly the youth) seem to have thought, “You say I’m the bad guy? Fine, I’ll be the bad guy.”

For example, people said the Right was racist, so the Nick Fuentes crowd emerged out of the woodwork, tossing around decades old statistics and dubious claims about African history without fear of reproach. The trendy phrase of the last few months has been “Black fatigue.”

So, the myth-making of the Left leads to thoughts like: we’re in immediate danger, everybody’s far-right, and the whole system is theirs. They kept on broadening the scope of who was implicated by their claims. What’s the Right’s myth of the Left? Well, they hate family, hate traditional values; they want you to stop being Christian, they want to take everything, weaken everyone, control the culture, indoctrinate the children.

And of course, this is only what the myths seem to claim, not what all individuals accept. I’ve said this in my essay on mass shooters: for the most part, this is just internet talk, this extremely tense divide between two sides where they’re an existential threat that requires a revolution—it’s mostly LARPing.

It doesn’t need to get physical. So the metamyth both sides seem to frame their individual myths with is: “We’re just play-acting. If we take over a part of Seattle or ‘storm the Capitol,’ all we really mean is, ‘golly, we’re angry,’ but we’re not looking to fight or nothing.”

The violent types are the people who don’t get the memo. They don’t know we’re all just playing pretend. They’re externalities of our social system, and that’s scary.

The Rise of Charlie Kirk

I remember watching Charlie Kirk’s rise. I remember when Turning Point USA was starting to get traction. Ben Shapiro was the king of debates, and basically ushered in a new era. “Ben Shapiro owns this liberal” and so on. The Daily Wire popularized the term “Leftist,” which was a level of specificity (as opposed to the broader “liberal”) which was admirable. In that era, other provocateurs popped up. Milo Yiannopoulos was about as far Right as you were going to see outside of 4chan or something. Shapiro was broadly constitutional conservative with a few “Neocon” positions (i.e. he was libertarian at home with more pragmatic foreign policy).

Then you started to see Steven Crowder pop up. You started to see more people doing debates. Andrew Klavan did a few, Michael Knowles did plenty, but not as big. Debate culture, especially going and debating on college campuses, was the big thing in the conservative movement. Then Charlie Kirk comes in. He hits the ground running: doing college debates, fundraising for Turning Point USA, putting on events for conservatives to speak at colleges, really trying to make an impact.

Steven Crowder gets the idea to do the “Prove Me Wrong” table. It was a big sensation, huge on the internet when it happened. It might be something like, “Abortion is wrong. Change my mind.” Anybody could come up, make their case, and he’d talk to them. It was very successful.

Establishment Republicans were wildly different than now; they were seen as placating the Left, conceding ground, never minimizing federal expansion, and so on. They called them RINOs (Republican In Name Only)—which worked really well, because former Speaker of the House, Paul Ryan, was considered the quintessential example in this era. Shapiro was, at that time, the radical; Daily Wire was the outsider. Then Daily Wire built itself into the establishment. Now, guys like Ted Cruz had to grow a beard and had to go talk on podcasts.4

The Shapiros, Knowles, Klavans, Crowders, and, to a lesser extent, Owens’ of the movement had finally settled in, and Kirk, about a decade younger than Shapiro, was right in the mix with them, and growing in stature.

Between Shapiro and Crowder, who were more or less the faces of the conservative college debate world, Crowder could be seen as harsher, with Shapiro being very direct, but less likely to look at the audience and mock you. Kirk was probably somewhere in between, and warmer than both in his general disposition.

And he took Crowder’s idea of “Change My Mind” and really perfected it. He grew to be a masterful communicator. Wonderfully articulate. A bit snarky at times, and he tried to box people in (i.e. over-framing arguments) for sake of brevity, but rarely egregiously so. I think fatherhood changed him for the better. His character was charitable and polite. People can say the opposite, but just go look at videos. He matches people’s energy, as Amir Odom pointed out. It’s hard not to get your feathers ruffled when you’re surrounded and someone’s being very rude. But I’d argue that he seldom even matched energy, but was usually an octave or two below, trying to de-escalate, while others escalate.

Policy-wise, Kirk was very similar to Ben Shapiro, as most constitutional conservatives were a decade ago. Eventually, conservative culture moved further right of the Shapiro position. What would’ve been radically conservative, in many ways Libertarian-but-not-quite, became moderate. And now people call it centrist—which honestly shocked me until I wrote this out.

Despite the Right’s position moving past Shapiro’s, Kirk (who didn’t budge) was still a rising star. The “Change My Mind” open table format being turned to open-air dialogue rallies captivated the youth, even more than Kirk’s predecessors had.

Kirk was also an outspoken and unafraid Christian, willing to argue for his beliefs in just as compelling a manner as his politics. He was a truly gifted autodidact, and the more I watch his debates, the more impressed I am with his gift for apologetics. This certainly aided his rise, as the New Atheist movement was on a decline toward death by the late 2010’s.

Moreover, as Michael Knowles pointed out, he could’ve been president. He had that political look. He had natural leadership. He had the ability to learn. He was principled. He was said to be the same behind closed doors as in public. He was charitable with his time. He was tall (don’t laugh, visual “above” placement is associated with perceived authority). He showed moral courage. People understood how impactful he was with the youth. He had their ear. He was no small part of the reason Trump won the recent election.

Even if people were further right, they all seemed to love Charlie Kirk. I had several students over the years who were obsessed with him. There were times I used him as an example of rhetoric I didn’t enjoy. I grew to like him more over time, but I definitely used him as a counter-example before.

So he’s an existential threat to the Left. To the Right, he’s the all-American guy—in many ways representing the best of American conservatism. Respectful, charitable, kind, principled in his faith, family man. Doesn’t budge easily, doesn’t concede ground weakly.

As all this played out, the Right saw Charlie as the one who engaged in dialogue. Now, I’ve seen the arguments from the Left that he wasn’t doing it in good faith. And, to their credit, in any recorded event like that, spectacle is going to be a factor in how you think/speak… but that went for his opponents as well (and many took advantage…one guy pretended to be Jesus). If they’d prepared more, they could’ve had a massive audience for a spectacle where they proved him wrong.

Charlie’s Controversies

The celebratory Left has responded to his death with, “Here’s a list of things he said that are bad.” Amir Odom did a great job contextualizing those and debunking the broader narrative. But even then, even if it were true, the idea that you make a list—“Here’s the guy, he’s spoken 10 million sentences on camera, I’ve got 25 where he really said something that, if I squint, proves he’s a bad guy”—what a bad way to think (and yeah, both sides do this too, it’s no good).

He explicitly said multiple times, things to the effect of, “Violence is unfortunate; I don’t support it. We need to get away from it.” Which is the exemplar I’d use to summarize his stance on violence.

Others summarize it as, “he’s supported violence many times!” Then, they find quotes as exemplars of that summary, and conclude that he deserves execution. It doesn’t matter that the individual quotes aggregated into the “he loves violence” summary have context-specific rationale which admit to violence as a concession/inevitability, rather than some good thing. It doesn’t matter that he said contrary things several times. It matters that whenever he said stuff, they only needed a few exemplars, because they could already infer the whole character/sentiment behind them, because they knew the mythos he was embedded in: existentially-threatening genocidal maniac.

If someone says anything besides “eliminate gun violence at all costs” when speaking about gun violence, and I already know that they’re a genocidal maniac, what’s motivating me to hear their words charitably and not assume they’re calling for violence? Not much.

The Storm Winds

The 1st Century

Here I want to borrow an image from N.T. Wright in, I think, Simply Jesus, talking about first-century Rome and the environment Jesus came into. He describes it as a storm with all these storm winds. You can think of the Pax Romana and the cult of Caesar as a wind, the longstanding messianic expectations of Israel as another, the tension between the Pharisees and Sadducees as another; you can think of the Roman disposition toward the Israelites, and the idea that the story of Israel is yet to be complete. They’re coming out of the intertestamental period where they’ve seen the extraordinary evil of the Seleucids, the unification of Israel under the friend of Rome turned king, Herod the Great arriving on the tail-end of a handful of disappointing false Messiahs, with some even believing that he was the Messiah, and the question on everyone’s mind was: when is God going to pick up where He left off?

All these storm winds are clashing together, creating this tempestuous environment. And that’s where Jesus comes on the scene.

The 21st Century

I want to borrow/apply this metaphor to the context of Charlie Kirk, because the main thing, in my estimation, is what’s happening at the level of cultural symbolism.

Note: I’m not saying Charlie Kirk was Jesus or anything close to that. I just happen to think this is apt imagery and I happened to read it in a book about Jesus instead of a book about someone else who was influential.

The storm winds of Left and Right were both whipping into a frenzy, especially in the wake of the sequence of violence, and somehow, Kirk found himself elevated very high. To the Left, the existential threat of the Right incarnate—moreover, if I’m right about us intuitively understanding that the masses hold more power than any individual, Kirk would, in many contexts, be a bigger threat than even Trump, because he was the best the Right had to offer the digital space. Moreover, he could’ve been the future, and he had a lot of the youth on his side.

The Right increasingly viewed him as the guy who went out and talked in good faith, willing to do something rare in our society: hear the other person out.

By many prior to his death, and many many more after his death, Charlie was considered the height of what conservatism had to offer. And what the conservative movement had to offer was the vision of America as it was envisioned by the Founding Fathers: a place of opportunity, liberty, freedom, and the open exchange of ideas. A place where disagreement and clash are built into the system, but violence is not necessary, because reason will prevail.

Imagine being at the center of this storm; imagine how volatile that position must’ve actually been. Terrifying.

Kirk was at the height of a yin-yang tension of two irreconcilable mythologies.

But luckily, we thought, those extreme mythologies really only exist in the digital space. Again, it’s all LARPing, and the reality is we see him as an influential man, but a man nonetheless. That’s all.

But that shooter couldn’t leave it in the digital space. He wasn’t content to LARP. And all at once, as Charlie went from apex to deceased to martyr, the Right took stock of the fact that he was the one they thought of when they thought of civil discourse.

That’s why so many articles have stated some version of “discourse is dead.”

It doesn’t matter that the Left didn’t perceive him as engaging in good-faith discourse. From the Right’s perspective, when you turn him into a martyr, you cement his legacy—that’s it, that’s the stamp on his life. And as much as you try to say, “Don’t turn him into something he wasn’t,” it’s not going to be effective. What he was or wasn’t is a fine debate, but unfortunately, nobody’s going to be keen on debating whether their interpretation of him as a symbol of debate is accurate, since he was executed while debating, for “spreading hate” by, you guessed it, debating.

He wasn’t allowed to simply fall out of grace with the Right, as has been the case with many leading figures: Shapiro fell out of grace, Owens fell out of grace, Peterson fell out of grace. Now, to the chagrin of many, he is not only in good grace, but he’s become the Right’s symbol of civil discourse.

Then, as evidence of some sort of collective possession by demoniacal forces, we saw the boots-on-the-ground Left act against their own self-interest and begin celebrating. They simply couldn’t help but give themselves over to their passions initially (now, there’re more reasoned, less passionate, arguments—which still suck—justifying his death).

From the perspective of the Right, it’s reasonable to ask, “Now hang on, if the avatar of civil discourse could be assassinated, who else can?”

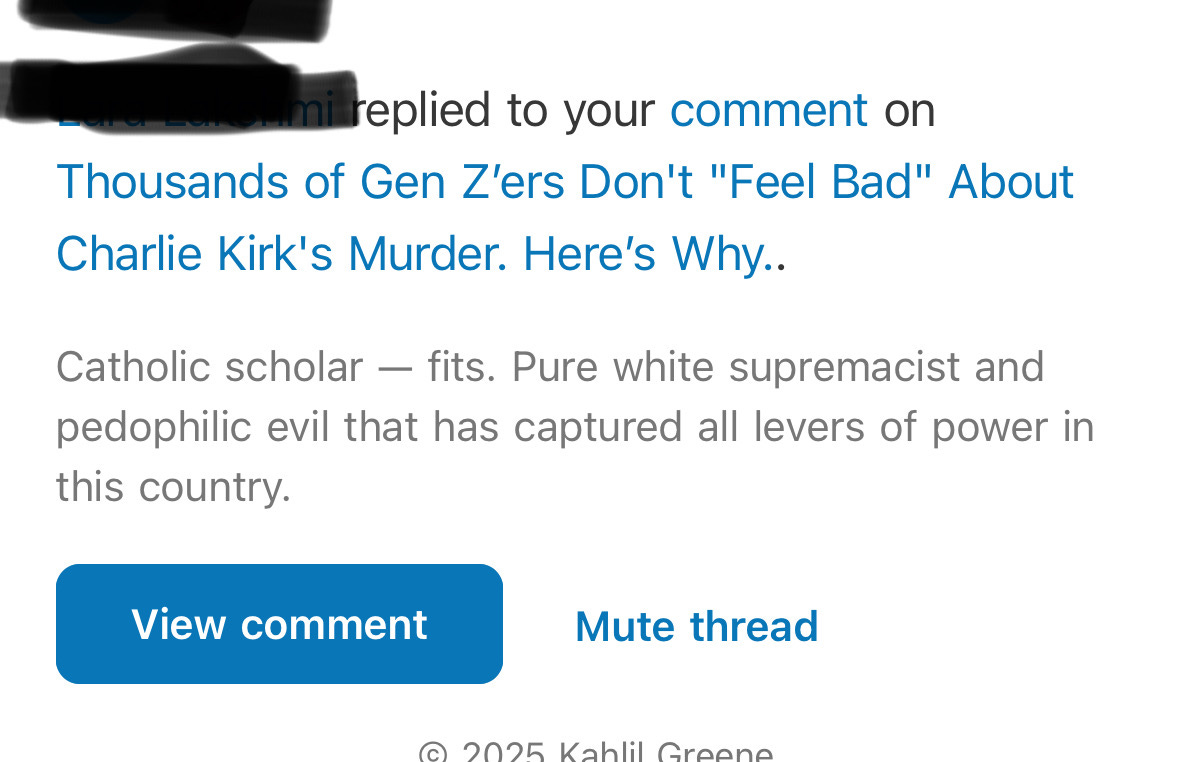

I saw this happen with me. I made a comment—I wasn’t expressing anything pro–Charlie Kirk; I was anti–Charlie Kirk death celebration—and somebody lumped me in with white supremacists. I noted, “Hey, I’ve never really been lumped in with white supremacists before” (possibly because I’m not white).

Thus, it became clear to me that in the post-Kirk era, semantic broadening hasn’t stopped or slowed. White supremacy can increasingly capture people of all races who hold a widening array of beliefs. In my case, I didn’t even have to say something nice about Charlie Kirk, I just said something negative about the people celebrating his death, and then she looked at my profile and saw I was Catholic. So, the criteria for this person (and the others who replied to me in support of her) for white supremacy-grouping are:

Thinks celebrating Charlie Kirk’s death is bad.

Is Catholic.

That’s a pretty darn wide net.

If you keep widening the scope of who’s implicated by terms like “white supremacist” and “misogynist” and so on, you shouldn’t also say, “and if you’re a white supremacist or a misogynist, it’s okay to kill you.”

Because if you don’t, then the operative question becomes: what outs does that leave the Right? Are we doomed to convert or die? Because many of the problematic political views align with traditional religious views, and that’s a problem for some of us.

This is why people can rightfully title posts, “Je Suis Charlie.” Evidently, we’re all potentially on the chopping block, and we just have to hope the Internet’s gaze never falls on us.

A Brave New World

So, we woke up in a new world where those things we had all been LARPing about in the digital space were reified at, in many ways, the highest level. At least the highest level in America outside of assassinating Trump.

When he was killed, it became clear he had built himself up to be carrying one of the largest symbolic burdens of anybody in the political sphere.

We all, but especially the Left, woefully underestimated the symbolic load Charlie was carrying. Many hoped to diffuse afterward with the usual ploys, “the shooter was on your side!” and “Kirk wasn’t good!” and so on. These are good moves—when you’re in a knockdown-drag out debate over some periphery issue immediately, and then another immediately after that, it’s hard to maintain energy for the original issue.

If the moves had worked, then this might not have been different after all.

But they didn’t, and it was. It’s been 2 weeks now, the timeframe everyone on Reddit gives for this sort of thing to pass, and it hasn’t. By that alone we can conclude that this is different.

Note: that was basically the end of the essay, and what follows is more of an epilogue, reflecting on how Kirk’s death lines up with some other, more Baudrillardian ideas I’ve been working through.

Epilogue

The Mangione Effect, Revisited.

So, what happens next? It’s fashionable to say, “Oh, nothing happens.” But as I pondered Kirk’s death, I questioned this.

The digital realm is extraordinarily good at diffusing our emotions. I imagine us as sine waves. It brings us up, it drops us down, and then we’re onto the next cycle. The frequency of these high oscillations of negative emotional energy is increasing. The upswing is increasing as well. And as a result, the externalities,5 those violent actors who don’t get the memo “keep this in the digital space where we all LARP” are increasing.

They’re increasing in frequency, yes, but even if they weren’t, it’s tough to argue that they’re not increasing in symbolic weight.

I mocked Luigi Mangione for thinking he could start a revolution, saying:

He thought that he could start a revolution, just like the mass shooters, by dealing a black eye to the quasi-divine entity… but there’s no revolution to be had.

He’s not the only one. Mass shooters often think they’re going to be the first fruits of a revolution, or that they’re participating in one. The harsh reality I mocked was that there’s no revolution coming. We pick it up, we move on to the next thing, and Mangione gets to be the most handsome guy in prison pulling pillow fluff out of his teeth.

But then I thought about how Charlie’s killer was labeling his bullets, just like the Minneapolis shooter and others before. Then, I remembered how the shooters would idolize a tradition of mass shooters. Then I thought about the first Trump assassination attempt, and I remembered someone saying at the time, “I hope this doesn’t open the door for more of these political assassinations.”

Mangione decided to execute a single CEO, but his target was, by his own admission, the healthcare system. He wanted to strike a symbolic blow, as though he could start a cascading revolution.

See, I think the Mangione Effect is to engage in symbolic killing—whether as assassin against a specific exemplar of a systemic issue, like Kirk, or against dehumanized masses of people who’re representative of a community perceived to be exalted by systemic issues, like the Catholic students in Minneapolis.

You say you want a revolution

I’ve referenced Jean Baudrillard extensively in my writings, and that’s where I’m coming from when I’ve minimized the likelihood of the Mangione Effect having any real disruptive ability. But I’m having second thoughts about this, because Baudrillard thought we were historically sui generis, subjected to a system of interpretation which was unlikely to be overthrown.

I’m not sure that’s the case anymore.

It seems like we are on an oscillating, but still upward trajectory of internal, political tensions. If we don’t develop more efficient systems to reduce these Mangione-esque externalities, who knows what might happen. If this is the case, then we’re not as unique as Baudrillard assumed, and are likely subject to the same historical logic as previous civilizations.

The problem with not being a sui generis civilization is that all civilizations seem to share one common trait: they fall. Revolutions happen; things change. Cultures get replaced. Invaders capitalize on instability. Civil wars occur. The culture goes into general decline until it peters out; whatever.

Charlie Kirk placed himself at the center of a storm we all feel stirring around us. The heights he achieved during his life and posthumously set his death apart, and don’t seem to have had any sort of satiating, cathartic effect on either the Left or Right. That is, despite his symbolic load, his execution didn’t mark some sort of end.

Rather, as Dilbert creator Scott Adams indicated, Charlie Kirk carried a great deal of energy with him, and on his death, it’s as though that energy was distributed to millions of others.

Perhaps, as some historians both ancient and modern believed, there’s a life-cycle to civilizations.6 If they’re right, then whether it’s rapid, like in a revolution or takeover, or a gradual decline, Charlie Kirk and his assassination will almost certainly be in the history books of any competent historian of the future. He’ll be remembered as an important figure, either as an underlying or immediate cause, to some shift in America.

Or, perhaps a more optimistic route can be taken. Maybe Charlie’s death showed the ineffectiveness of silencing opponents with a bullet, and all those who’ve sought to take up the mantle of civil discourse will turn the tides a bit. Some of that perpetually distributed angst of the internet will manifest in real life, but through heated arguments, instead of symbolic violence.

It’s calmed down now, so far as I can tell.

If somebody adds a lot of clarification, it almost doesn’t matter, because the person who opposes that idea won’t read it; they’ll read the summary from someone on their side who (probably intentionally) excludes the clarifications, the tone, and any other nuance vainly attempted. This obviously leaves us vulnerable to lies by omission, and it’s increasingly relevant in how we engage one another and consume information.

A quick aside about these comparisons being used as arguments against the significant response to Kirk.

First, the Democratic legislator who was shot alongside her husband in June, as this has been a common response from folks on the Left, “why wasn’t that a big deal?!” Well, it is a big deal. But platform, reach, significance to the culture are all factors to consider (and are, indeed, no small amount of what I hope to discuss herein). As does, obviously, the fact that Charlie Kirk was shot at a giant event in broad daylight while speaking and the video circulated instantly.

Another comparison is to the Trump assassination attempts. Well, these will obviously feel different because they weren’t successful, but also, as Brett Cooper pointed out, there’s something about the fact that Trump was in an actual political office. He’s in the seat of power of the Western world and is the most controversial man on the planet. We, unfortunately, have a ready-made category for that sort of thing: Lincoln, Roosevelt, Kennedy, Reagan.

Not even dissing him here. The beard is cool, and Ted Cruz is great. He’s Cuban.

I’m describing shooters as externalities of the social system we’re all a part of. Thinking here of the people who, like Neo and his predecessors in The Matrix series, are unavoidable (if systemically undesirable) exceptions to norms. The ones for whom the temperature raises itself too high, and they seek a way out which affects others. The suicidal, or the sort that flee off the grid might also fit in some broader definition, but I think the ones who threaten the social system itself are a best-fit.

Here, I think of Polybius, Vico, and Spengler. I think Machiavelli could be on this list as well, but I don’t really remember anything he wrote very well.