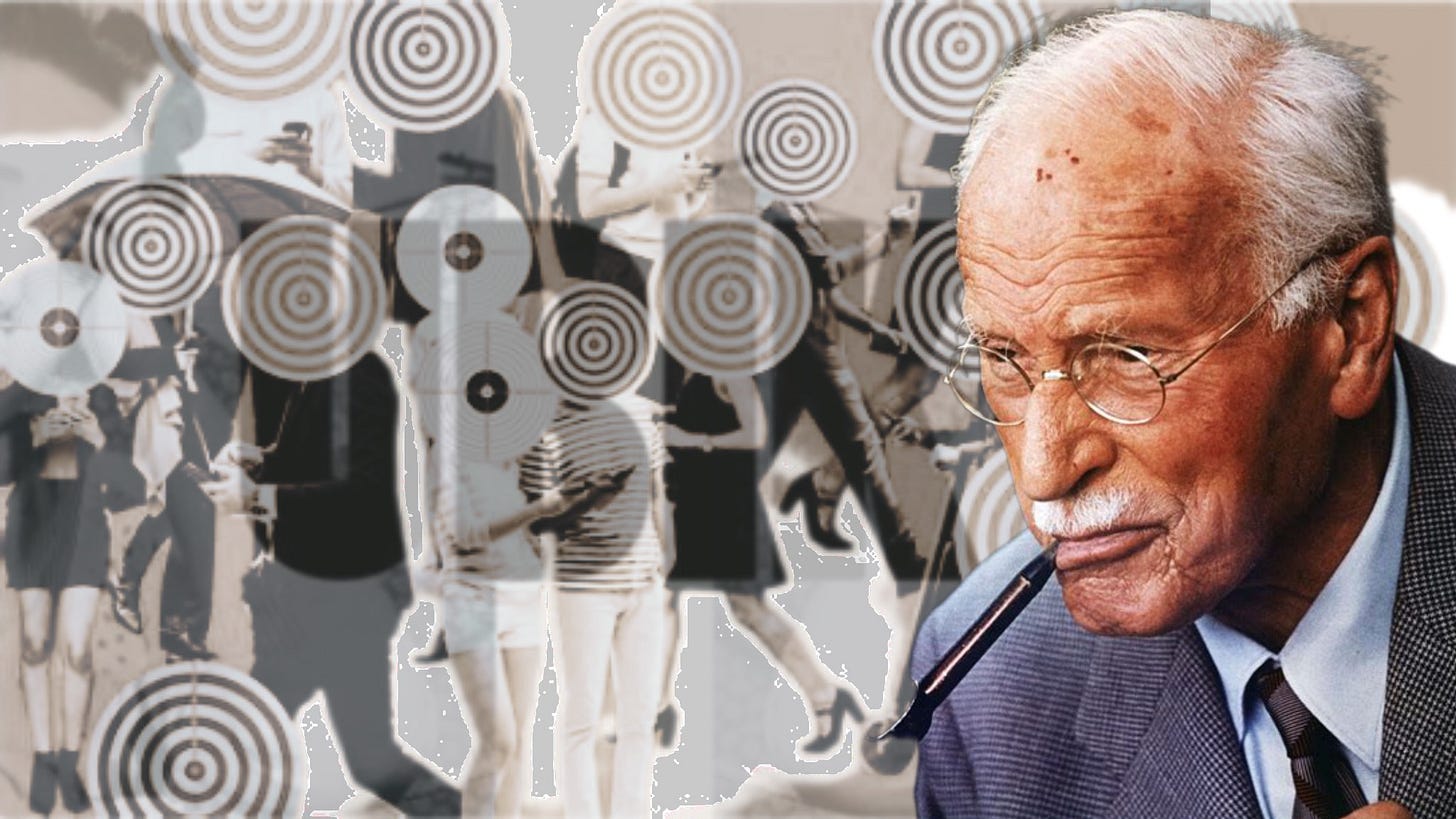

Consumer-Grade Synchronicity

A Jungian perspective on targeted ads and their disenchanting effect

Everyone knows what a targeted ad is. Most of us have experienced that uncanny feeling of having just talked about something, only to find an advertisement for something eerily similar popping up. It might be on YouTube, on Social Media, or on some random website. But it’s happening all the time, and our profiles are getting more sophisticated by the day.

There’s a whole range of metrics go into building our user profile. If you share data between apps, the profile gets even more precise. I’ve even heard that proximity plays a role—that if you spend a lot of time around someone who’s a professional skier, you might get ads for skiing gear or winter sports. Whether or not that’s true, I don’t know.

But what I do know is that I’ve had countless conversations with people who felt as though they were being watched. They’ll say the ad was just too perfect, too timely. It had to be monitoring them. And while I’m not primarily interested in the technical mechanics behind that perception, I am interested in the psychological phenomenon that emerges in that moment; what Carl Jung would call synchronicity.

A Quick Aside

Candidly, a reason I felt motivated to write this is because I’ve noticed a growing trend of anti-Jung sentiment in Christian communities. And I get it. I’ve never believed we should rely heavily on Jung as a Christian theologian.

But I’m also wary of the way entire intellectual figures get swept aside with hand-waving dismissals. That reflex doesn’t seem to primarily come from deep disagreement. It seems more like a psychological convenience—a shortcut to reduce the world’s complexity by writing off large bodies of thought wholesale. There’s empirical support for that notion, but I digress.

Synchronicity

Jung co-authored a book called Synchronicity with the physicist Wolfgang Pauli. What they tried to do was explore a non-causal relationship between an event and the individual observing it.

The link between the physical and the mental in these events is meaningful; in fact, it’s the meaning itself. It’s an acausal connection—something that couldn’t be explained by traditional cause-and-effect reasoning. That’s why Jung brought Pauli into the conversation: to explore how this kind of relationship might mirror the strange, non-linear interactions observed in quantum physics. The broader hope was to find a concept that could help bridge the gap between the physical and social sciences.

In Synchronicity, Jung cited cases where patients dreamed of a symbol—most famously, a golden scarab—only for a similar symbol to appear shortly afterward in the external world.

In the scarab case, as the patient was describing the golden scarab in the dream, a tapping was heard on the window. Jung opened it and a bug flew in, which he caught and presented to the patient. Shockingly, it was a scarabaeid beetle, which is the closest European equivalent to a scarab, and not native to the area.

Standard glib explanations don’t work very well here. There’s no evidence that the patient saw the beetle and subconsciously incorporated it into her dream. There’s no reason to assume the patient was lying.

Obviously, there’s also no evidence that the dream somehow summoned the beetle.

But there is an effect. The patient, who was described as educated and overly-rational, found the event extraordinarily meaningful, and it helped to break her of her excessive rationalism.

Jungian Unconscious

Jung’s idea of a “collective unconscious” describes a shared reservoir of archetypes and symbols present across all of humanity. That doesn’t necessarily require a metaphysical commitment; in fact, for Jung and especially his successors, it’s framed in evolutionary terms. The archetypes arise from recurring psychological and environmental patterns embedded in human cognition. Whether this is purely social evolution a la Erich Neumann, or something physically innate is still an open debate in Jungian scholarship.

Whatever the nature of it, the collective unconscious is described as interacting with the individual’s conscious as well as the physical world. Here, Jung deliberately avoids mechanistic explanations for this interaction. He emphasizes the ambiguity and preserves the mystery of synchronicity. However the interaction occurs, the synchronicity lies in the subjective experience of meaning; how the individual interprets the event in light of prior symbolic content.

Now, you don’t have to accept Jung wholesale to assent to this. Strip away the collective unconscious and the phenomenon still stands psychologically. It’s simply the subjective experience of seeing something as meaningful, especially when it’s personally symbolic or emotionally charged. There’s nothing particularly controversial about that.

If you dream, talk, or think about a rare symbol and then encounter it in real life under unlikely circumstances, you’re likely to interpret that experience as meaningful. The mind is attuned to value-laden information. That could be something emotionally encoded in childhood (a particular smell, a meal, a tune, etc.), or it could be something whose meaning is generated by timing, improbability, or the sheer “rightness” of the moment.

Algorithm as Oracle

So, what is it that these targeted ads are doing?

In some ways, they’re simulating synchronicity. They’re crafted to appear symbolic and feel like they arise from inexplicable connections. It’s not just that you wanted a thing and saw an ad. It’s that the thing appears, just in time, just in the right place—almost as if it’s responding to some deep need. Just like the scarab beetle showing up for Jung’s patient, these ads show up right where you are.

We know why this happens, of course. The platforms know where you’re going to be. They’ve gathered data. You’re on Instagram, Facebook, whater. They know your behavior patterns. That part’s not mystical.

Moreover, as our profiles become increasingly accurate, algorithmic abilities to predict needs we haven’t yet expressed will become increasingly sophisticated. You like music, you like swimming—hey, did you know there’s waterproof headphones? Now the advertisement isn’t simply reacting to wants you’ve expressed online, but to things you may want, based on the aggregation of a great deal of your personal data.

Disturbingly, this structure mimics the architecture of Jung’s theory, but in a mechanized, externalized way. If you rejected Jung’s idea of a collective unconscious as a biological or cultural evolution, you’ll now get to see one anyway. This one doesn’t emerge from millions of hard-won adaptations across several generations and cultures, but more from millions of (maybe) hard-won adaptations across between 1-3 generations, mostly originating from, let’s face it, not very many cultures.

We can squabble about the details of that generalization, but we can all agree that its telos is fairly simple: money.

I’m not here to attack money, I wouldn’t mind some more of it myself. But I’d imagine few of us think that it’s the best basis for a system of interpretation.

Ad Effects

Unlike Jung’s model where the connections are mysterious and acausal, with targeted ads the system is fully causal. There’s a logical series of inputs: your behavior, the behavior of people like you, your proximity, your language, your micro-expressions, your click habits.

The effect of the ads has a potential and an aim, however unwittingly (I’m not convinced that there’s a lot of mystically-minded technocrats writing algorithms), to feel just as mystical. For a few reasons, this is where it seems to become rather worrisome.

The systems are hijacking the very areas our mind built for enchantment and reorienting them toward consumerism. So, if there were something sacred meant to be accessed by those areas, what happens when they’ve been colonized by algorithms and monetized by platforms? More clearly: what if we reorient our desire for a meaningful, enchanted world toward these pseudo-synchronicities under false pretenses—what if we’re duped?

But even worse, and I think far more likely: what if we're not so naive as to believe in providential product placement. We know that it's a targeted ad, and we know, to some extent, how and why it works.

We’re probably not fooled into thinking this is a mystical connection; so, when this plays on our mystical intuition that would otherwise lead us to find meaning in synchronous events, its effect is, instead, a conditioning. Conditioning us to see coincidence at best and exploitative targeting at worst. To assume any meaningful connections are problematic misreads.

It's like an active training in disenchantment.

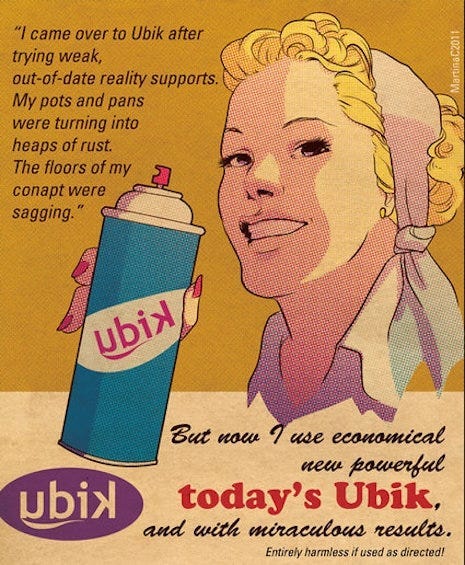

I’d like to extend a special thanks to our sponsor, Ubik!

Perk up your morning with Ubik cereal, the crunchy whole-grain breakfast that starts your day right! Packed with energy to keep you going strong. Safe when taken as directed.