Oblivion from The Elder Scrolls as a Reimagining of Hell for New Age Individualists

A few years ago, I spoke at the Mythopoeic Society’s “Fantasy Goes to Hell: Depictions of Hell in Modern Fantasy Texts” about Hell in The Elder Scrolls. The presentation wasn’t long enough to engage the lore properly, so this is a lore-expanded adaptation of that presentation.

The Worldbuilding of The Elder Scrolls

The Elder Scrolls (TES) series is a high-fantasy role-playing video game franchise developed by Bethesda Game Studios. While its first two titles, TES: Arena and TES II: Daggerfall had a relatively limited following, its latter 3 main titles, TES III: Morrowind, TES IV: Oblivion, and TES V: Skyrim are all award-winning. The franchise has also generated multiple spin-offs, with its most popular being a massive multiplayer online (MMO) role-playing game (RPG), The Elder Scrolls Online.

While there are several popular video game franchises, TES has a unique staying power and community. In fact, much of its success may be attributed to its active community, which enjoys watching gameplay, theorizing, and especially modding (fan-made modifications and additions to the game software). There seems to be no end to the potential exploration of TES universe.

However, one of the major contributors (perhaps the) to its staying power is its extremely intricate lore and worldbuilding. The series draws on several real-world influences, both Western and Eastern, both philosophical and theological, in order to weave together a truly fascinating place.

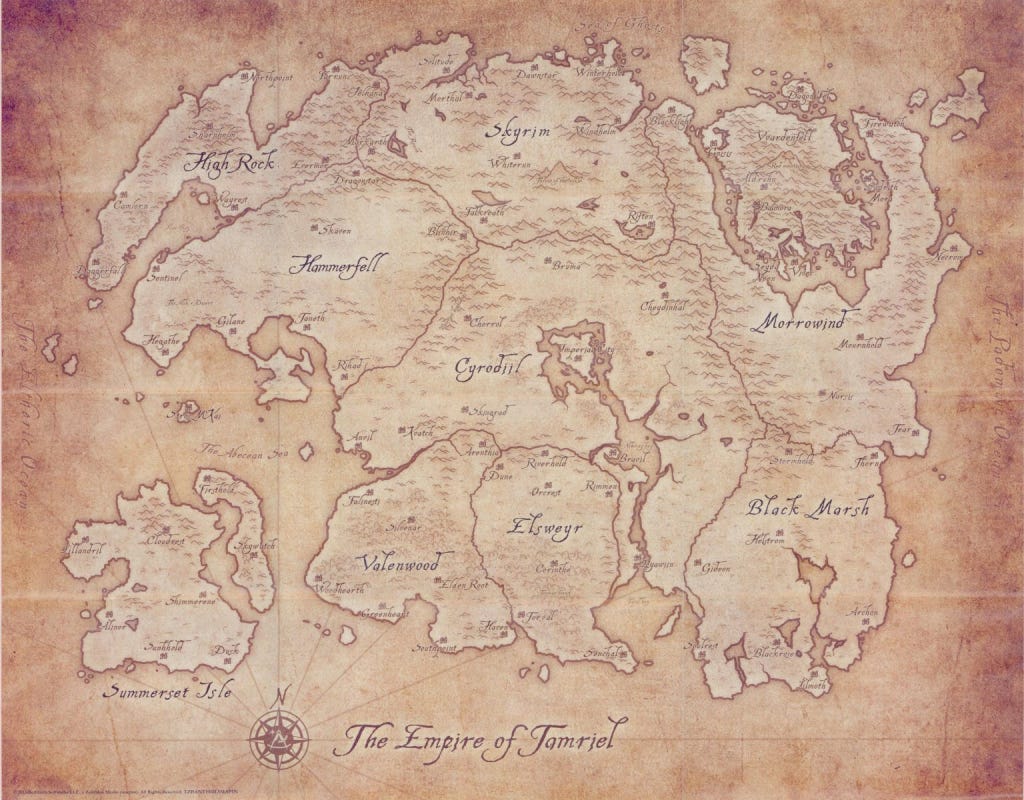

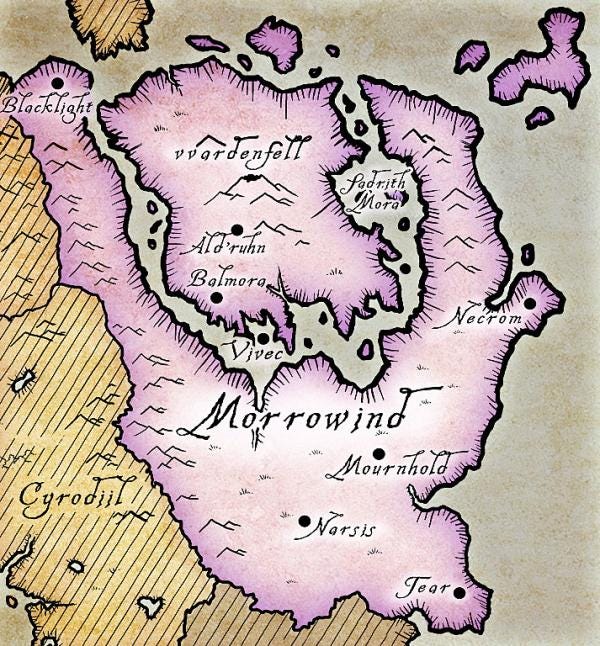

Nirn (the world where TES takes place) has borne witness to countless wars, competing factions, great warriors, mythical figures, and spiritual entities. As players traverse Tamriel (the continent on which all TES games take place), they are given constant reminders that they are in a world rich with history and significance.

In a Tolkienesque fashion, TES has imbued locations, artifacts, and people with layers of historical data.

Red Mountain in Morrowind, for example, is not only the site of a great battle in Morrowind’s history, but also hearkens back to the prehistoric Dawn Era, where it emerged from the heart of a dismembered deity.

The battle-axe Wuuthrad is split into shards by the 4th Era when TES V: Skyrim takes place, but it was wielded by the Nord hero Ysgramor during the Merethic Era, when he and his 500 companions freed Skyrim from the grip of the Snow Elves (Falmer).

The Khajit nomad Ma’iq the Liar is a fan favorite, recurring in TES III-V as well as TES: Online. The aptly named Ma’iq the Liar spews false facts and odd opinions as he travels Tamriel; whether he is over 1,000 years old or is part of a long line of Ma’iqs who have been doing the same thing for at least 1,000 years, he is an exemplar of these layers of history embedded within TES.

These histories, much like those of the real world, often blur the lines between the transcendent and the mundane. In a manner reminiscent of The Histories of Herodotus or the story of Israel, the history of Tamriel is as much a history of divine intervention as it is about the people.

The annals of Tamrielic history are absolutely replete with instances of divine forces intruding on and influencing Mundus (the mortal realm). These intrusions can be as minor as whispering to an individual, and as major as a direct invasion of Mundus or the use of anchors to drag the mortal plane into Oblivion.

The great Red Mountain of Morrowind, home of the Dark Elves (Dunmer) rose from the land when the heart of the dismembered god Lorkhan was tossed onto the ground. Later, that very heart was used by the warriors Vivec, Sotha Sil, and Almalexia to become living gods, calling themselves “The Tribunal” and provoking the wrath of the vengeful deity Azura.

For the denizens of Mundus, the divine has been an immanent part of life, for better or worse, at all points in their history.

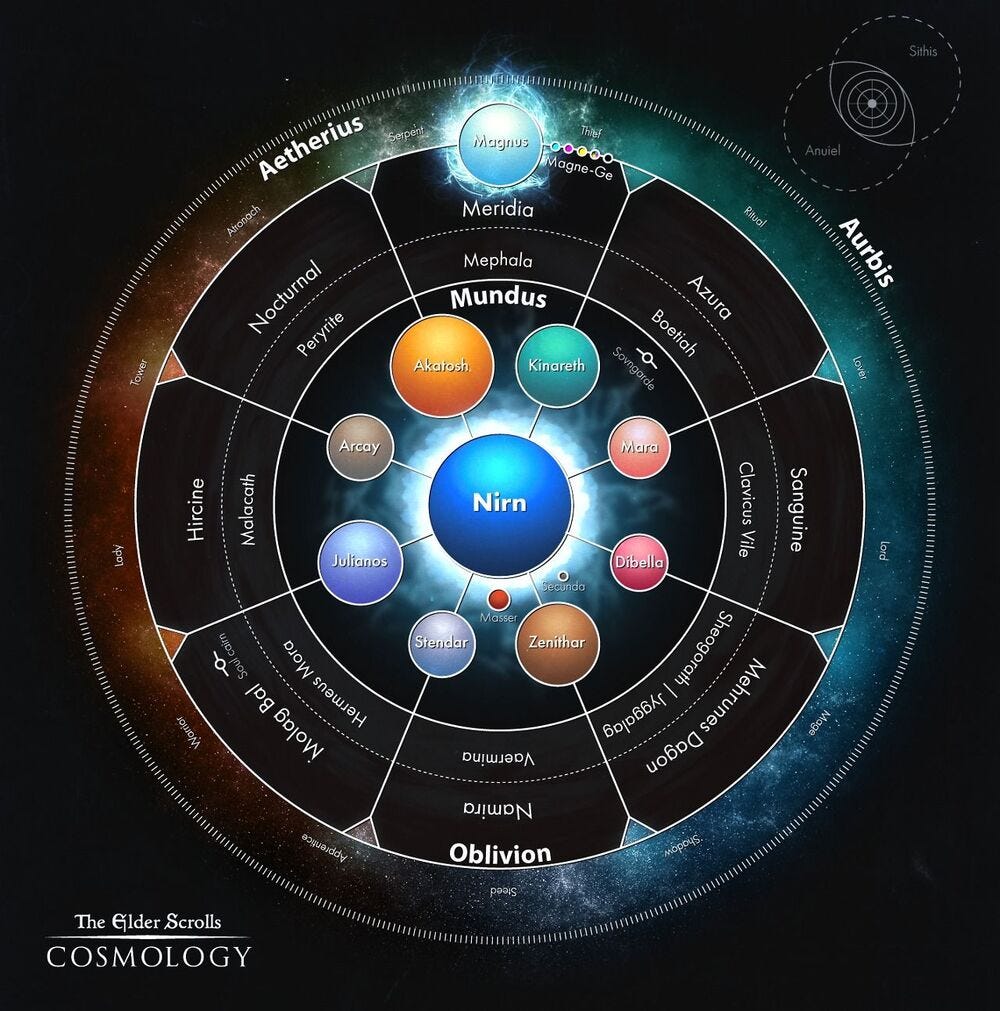

Mortals must constantly be on alert for these intrusions. Mundus is, quite literally, surrounded on all sides by Oblivion, or, as some call them, the “demonic planes.”

Where C.S. Lewis’ The Great Divorce portrayed Hell as only appearing large due to an error in perspective, but in reality, only fitting onto the tip of a blade of grass in the heavenly landscape, TES portrays their hellish landscapes as larger, more powerful, and of an unknown, possibly infinite number. The inhabitants of these outer realms are called “daedra,” and most mortals count themselves lucky if they never encounter one.

Others, however, seek to summon them from Oblivion into Mundus to fight on their behalf. Others, such as the Dunmer, consider some daedra to be good. Azura, for example, is a Daedric Prince, meaning that she rules over her own plane of Oblivion. Still others, such as the Ideal Masters, endeavor(ed) to leave Mundus and inhabit, and even rule, a plane of Oblivion. In fact, one of the most popular theories as to the sudden disappearance of the dwarves (Dwemer) at the Battle of Red Mountain is that they were transported to Oblivion.

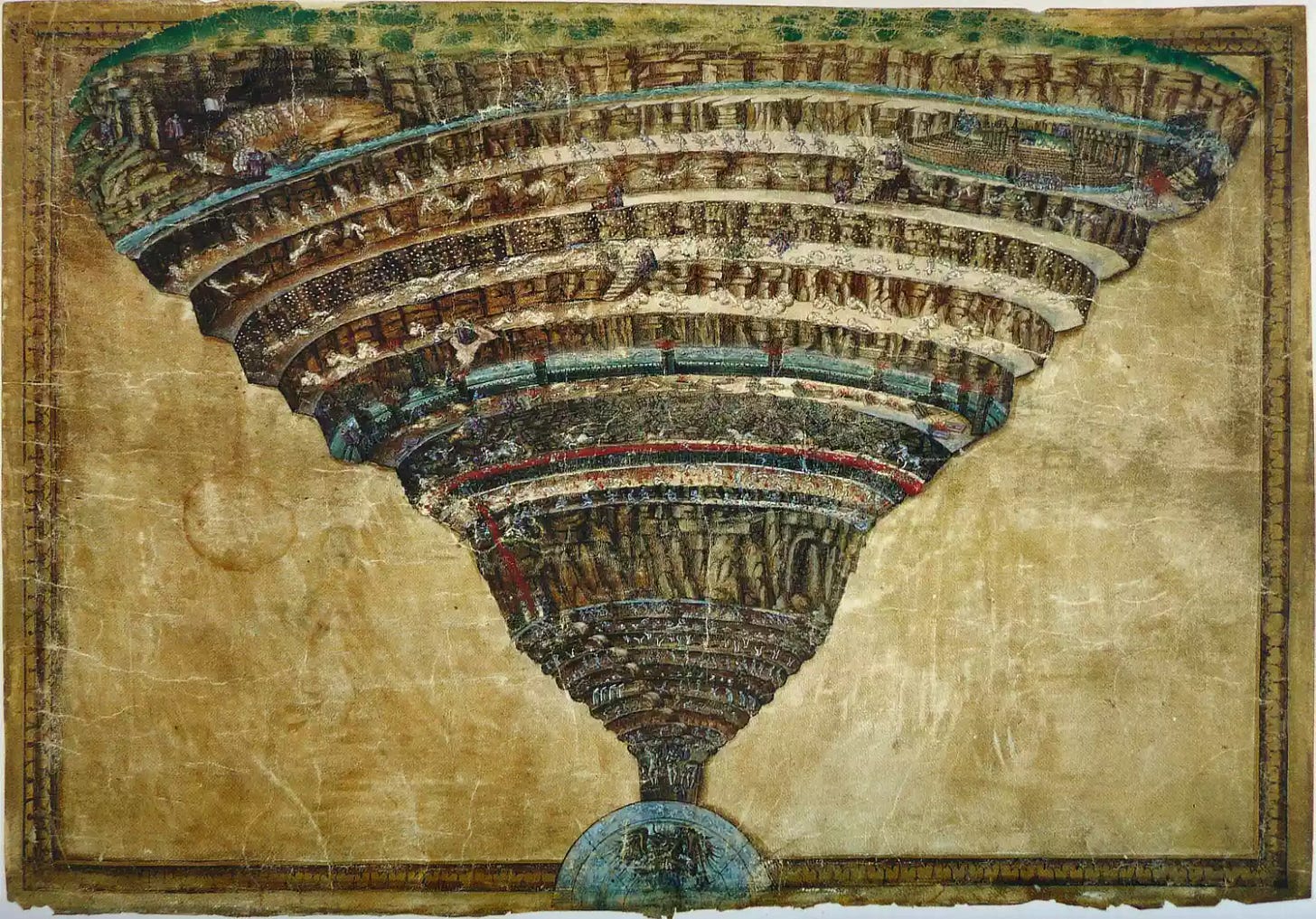

If there is a Hell in TES, it is the planes of Oblivion. But as is hopefully apparent, Oblivion is not interpreted by many citizens of Tamriel as monolithic, nor is it portrayed to the player as such. The Daedric Prince of domination and enslavement, Molag Bal, also called the King of Rape and the Lord of Lies, rules over the plane of Oblivion called Coldharbour. This chilly realm of chains, torture, and souls ever-descending further into madness is about as close to the lowest level of The Inferno as any game has come, other than, of course, the video game Dante’s Inferno.

However, the Shivering Isles, ruled by the Daedric Prince of madness, Sheogorath, can range from dangerous to outright silly. For the humanoid daedra who inhabit them, they are home. The Soul Cairn, ruled by the Ideal Masters, is entirely unpleasant for the souls trapped there without hope of escape. However, the Ideal Masters were once mortal necromancers, and it became so unpleasant because they captured souls in order to empower themselves—and empowered they are.

A World, Inhabited

How are we to account for this place, Tamriel, where millions of players have spent many millions of hours inhabiting? It is a place where the player keeps being tossed into major historical events, where both martial forces and spiritual forces are a threat. Where we find gods whose worship grants benefits, but also Daedric Princes able to grant more powerful and direct benefits. The influence of Oblivion is an ever-present reality for citizens of Tamriel, including the player, and it is simultaneously held to be a place of hellish torment and a place of unbounded opportunity.

While TES appears to engage in mythopoesis, and certainly introduces many a novelty without direct real-world parallel, it is still drawing from and responding to various cultural influences, just as Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings engaged in mythopoesis while still drawing from Western cultural tropes, philological interests, Anglo-Saxon lore, and Catholic narratives.

Because of the unique worldbuilding of TES, where the spiritual is as important and at times more important than the material, its portrayal of Hell, Oblivion can’t be relegated to the periphery.

The Metaphysical Backcloth

The Evolution of Hell

In Western Christian thought, there has been an evolution of our collective perception of the landscape of Hell. It’s a complex topic. Though cross-culturally present in various forms, the Western version is expressed in Biblical passages, and has undergone several interpretations and iterations.

In the Old Testament, “Hell” is usually translated from Sheol, which is just the grave or the pit. The Septuagint would translate this to “Hades,” which is also used throughout the New Testament and described as a place of being tormented in flames (Luke 16:24). So, for Hades, we see it having the flexible use of being both a general place of the dead, not a place of punishment, and a place of flaming punishment. We see another flame reference in the New Testament to Gehenna, based on the Valley of Hinnom, wherein the Israelites had, in the past, sacrificed children by fire to the god Molech. Later, it would continue to be a place associated with fire, being a garbage-burning dump by the time of Jesus. Throughout the Intertestamental period, it did indeed have a more spiritual connotation to it, being considered the place of punishment after death. The word Tartarus is also translated into Hell, which was a Greek place of punishment after death and is portrayed in the New Testament as a place of darkness.

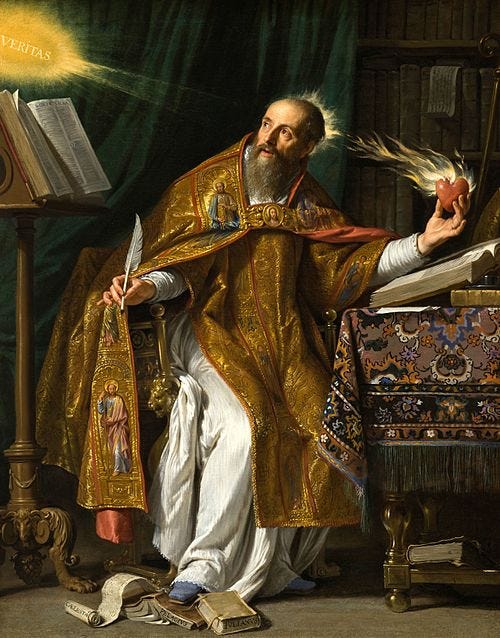

The earliest Christians offer little insight into the nature of Hell. While Hell is referenced throughout the Bible, its nature and landscape simply were not topics of discourse for the Apostolic Fathers. The broader Patristic Era would come to discuss Hell more often, but opinions were not monolithic, and during this era, the differences in Eastern and Western theology became pronounced. In the East, figures like Gregory of Nyssa and Origen championed apokatastasis, the restoration of all things in creation, which was extrapolated to imply non-eternality of Hell, and in Origen’s formulation, even the restoration of the devil. In the West, the most looming figure was Augustine, of whose work it has been said that all Medieval theology is but footnotes. Augustine argued for both the eternality of Hell and its nature as a place of torment, and these stamps stuck.

By the Middle Ages, the great systematizers that were the Medieval theologians were balancing Augustinian theology with Greco-Roman thought, culminating in likely the most famous portrayal of Hell in history: Inferno, by Dante Alighieri from The Divine Comedy. In Inferno, Dante embarks on a descending journey through the layers of Hell, an enduring concept that was influenced by Medieval cosmology, which believed in concentric circles of the Cosmos. That cosmology was influenced by Aristotle’s cosmology. Additionally, many of the things and characters Dante interacts with in Hell are influenced by The Aeneid, which is written by the Roman Virgil, who serves as Dante’s guide through Hell in Inferno.

Homer captured Greek thought of the 8th century BC, Virgil took direct inspiration and influence from Homer and then reimagined it in the context of Roman thought, then Dante took Roman thought and adapted it to Christian thought. This thought was bounded by a Christian cosmology that had also been lifted, in part, from the Greco-Roman world. Dante, therefore, gave us an image of Hell as a place of long-suffering, riddled with severe, sometimes ironic punishments, and an abandonment of hope nested within a hierarchy based on severity of sin.

This image has affected countless subsequent portrayals of Hell, as well as the cultural consciousness regarding it. Even without reading Dante, many of us have been made aware of these tropes.

The New Age

New Age spirituality is a complex belief system that actively resists a singular definition in its avoidance of dogmatism. It can, however, be characterized by thematic patterns, even if not by explicit doctrine.

Historically, it gained significant traction during the 20th century, where it often acted as a counter-cultural force, both critiquing traditional religious narratives and introducing Eastern thought into the West. Its name is derived from a prediction of an impending New Age, as predicted by Madame Blavatsky of Theosophical Society fame. This era would be welcomed and guided by hidden overseers called the Ascended Masters

This shift toward non-Western belief encourages embodiment—the experiential. Since its inception, some of its tenets have been integrated culturally, making it less of a counter-cultural influence and more of a culture-defining influence. The theosophists were a sect of Western esotericism that emerged in the 19th century, alongside Freemasonry. Of note in theosophy is a certain amount of Eastern influence from both Buddhism and Brahmanic traditions. This expectation would develop and grow until 1970, when David Spangler announced that the New Age was imminent as a result of waves of spiritual energy. Thus, followers would endeavor, in a manner characteristic of New Age spirituality, to engage in practices that would facilitate their own spiritual growth and transformation. By this collective spiritual ascension, the New Age would come.

As a means of attaining spiritual growth, New Age practitioners eclectically borrowed from various sources of ancient wisdom and esoteric tradition. Practitioners have an affinity for gnosis, the attainment of secret knowledge, as well as Merkabah mysticism and Kabbalah, which all make frequent appearances in New Age circles. New Age thought frequently reinterprets established religious figures and narratives, such as Jesus Himself. Jesus is reimagined as masking the deep, esoteric messages within his more superficial and accessible messaging. Their selective incorporation and reinterpretation of religious texts and beliefs extends beyond Christianity into Judaism, Buddhism, and Brahmanism, just as their predecessors had. This broad range of influences demonstrates the holistic inclusivity of the New Age, which it views as entirely lacking in formal religious institutions.

Finally, it is integral to the New Age that mysticism is not only personal and subjective but a reflection of a deeper reality of the world. The New Age is ushered in by spiritual currents that individuals can both tap into and influence. The Law of Attraction (LOA), whereby one’s beliefs and thoughts have the power to manifest realities, exemplifies this. The LOA suggests that reality itself is shaped not simply by material action and causality but by capital “C” Consciousness. Or, as Hermes Trismegistus (an important figure to the New Age) has claimed: All is mind. The New Age can be characterized as a sort of mirror or foil to the secularization of the West. It both diverged from and engaged with mainstream thought.

Individualism in the West

In Western civilization, the concept of individualism has been a steadily ascending narrative, undergoing significant mutations at different points of history. Arguably, the most significant shift occurred during the Enlightenment era of the 17th and 18th centuries, which ushered in new emphases on individual liberty, rational inquiry, and skepticism toward established authority. René Descartes, for many, marks this transition with his Cogito, ergo sum (I think, therefore I am) acting as a foundation on which he could construct a philosophy centered on the self as an autonomous reasoning entity. This was a departure from premodern frameworks that often subsumed the individual within broader communal or metaphysical contexts.

The Enlightenment's elevation of the individual found political expression in the works of philosophers like John Locke and Thomas Hobbes. While both advanced the concept of a social contract as foundational to civil society, they differed markedly in their views of human nature and the role of governance. Locke's emphasis on natural rights and limited government resonated with American revolutionaries, greatly influencing the intellectual backdrop of the founding of the United States. The Declaration of Independence, in many ways, epitomizes this ideological shift; its claim that it is “self-evident” that “all men are created equal” starkly contrasts the hierarchical, often feudal arrangements characteristic of premodern history.

By the 20th century, individualism had entrenched itself in the Western consciousness.

Enter postmodernism. This movement both expanded this conversation and problematized it. They questioned the overarching narratives (metanarratives/grand narratives) that modernity confidently posited, replacing optimism with skepticism about humanity's progression toward prosperity.

For many of these Frenchmen, history was not a linear trajectory but a series of oft-disconnected events and emphases that are post-facto woven together by the powers-that-be. However, historical accounts were not the only target, but even the very mediums through which they’re conveyed: language and institutionalized forms of knowledge. This stance would contribute to what could arguably be called a climate of epistemic uncertainty. Consequently, this heightened form of scrutiny paved the way for a renewed emphasis on the individual, now seen as a site for potential liberation from oppressive affiliations and categories.

Within most thought we designate as “postmodern,” reality is not so much unknowable as it is complex and presented in a biased fashion to us—it’s a multiplicity of subjective experiences that resist unification into a singular truth. This acknowledgment of the subjective nature of experience accentuated the individual's role as interpreter, thereby adding another layer of complexity to Western individualism. It introduced an individualism that was not merely about autonomy but also about the recognition of ambiguity and relativism as intrinsic aspects of the human condition.

The Backcloth Itself

In The Discarded Image, C.S. Lewis discusses the Medieval culture that birthed Medieval literature. One oft-overlooked point he makes is about Medieval cosmology as a “backcloth” of the era—an underlying set of assumptions about the way the universe is. TES is, like Medieval literature, an art piece which draws from a backcloth; only this backcloth is individualistic and New Age-influenced.

Or, more precisely, if the Western backcloth of the 20th and 21st centuries contains a plurality of beliefs, but is fundamentally individualistic—one section of that pluralistic backcloth contains New Age beliefs.

New Age thought had largely given way by the 1980s to new forms of spirituality, but its presence had left a mark. New Age ideas had made their way into the broader culture, with mainstream acceptance of “mindfulness” as valuable, for example. However, the seeds were already growing for some of the more esoteric beliefs like a belief in spiritual energy, psychics, reincarnation, and astrology.

It’s relevant to note here that the New Age movement largely rejects the idea of Hell. However, traditional formulations of Hell exist within the Western cultural backcloth, even if they are not taken to be accurate. Moreover, the postmodern world that characterized the late 20th century was part of the “secular age” described by Charles Taylor, and its people are largely “buffered” to the spiritual. Thus, the backcloth of this age contains diverse elements and descriptions of the metaphysical, but by default rejects them.

The premodern Christian worldview has long since fallen out of vogue as a predominant backcloth, but it has, in the formulation of Bishop Robert Barron, been fractured and spread across the culture, so that semina verbi, or seeds of the Word, are present throughout the West. That is, symbols, narratives, characters, and other elements of Christianity can be found in numerous places in the culture, even if the culture neither recognizes them as such nor has an interest in their origin. For example, Barron describes Girardean scapegoating in The Hunger Games and finds a Biblical view on the treatment of “the Other” in District 9.

The backcloth of late Modernity contains all manner of elements that have been stripped of original meaning and context, and for the artist or writer, these are a goodie bag of materials to be used for their projects. But, where a characteristically postmodern artist would likely use them in a subversive way to blaspheme, undermine, or raise questions about their original context and meaning, fantasy creators like those of TES draw from the backcloth in an earnest appreciation of its contents.

But that doesn’t mean that the contents aren’t still disparate; the icy landscape of Dante’s lowest circle resembling the most hellish plane of Oblivion, Coldharbour, is likely no coincidence. But, this does not imply a genuine use of an orthodox (note the lower-case ‘o’) Christian concept. Rather, the image, affect, and overall aesthetic are borrowed without any necessary loyalty to their origin. As TES crafted their demonic planes, they utilized various disparate elements, some Christian in origin, but they are repurposed, as Dante did with his Christianization of Greco-Roman mythology, into a New Age, individualistic mythology.

The Creation Myth

In the lore of The Elder Scrolls series, few figures are more prominent than the trickster Lorkhan.

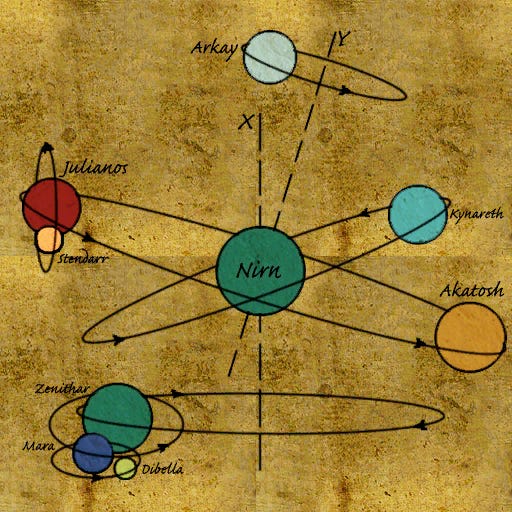

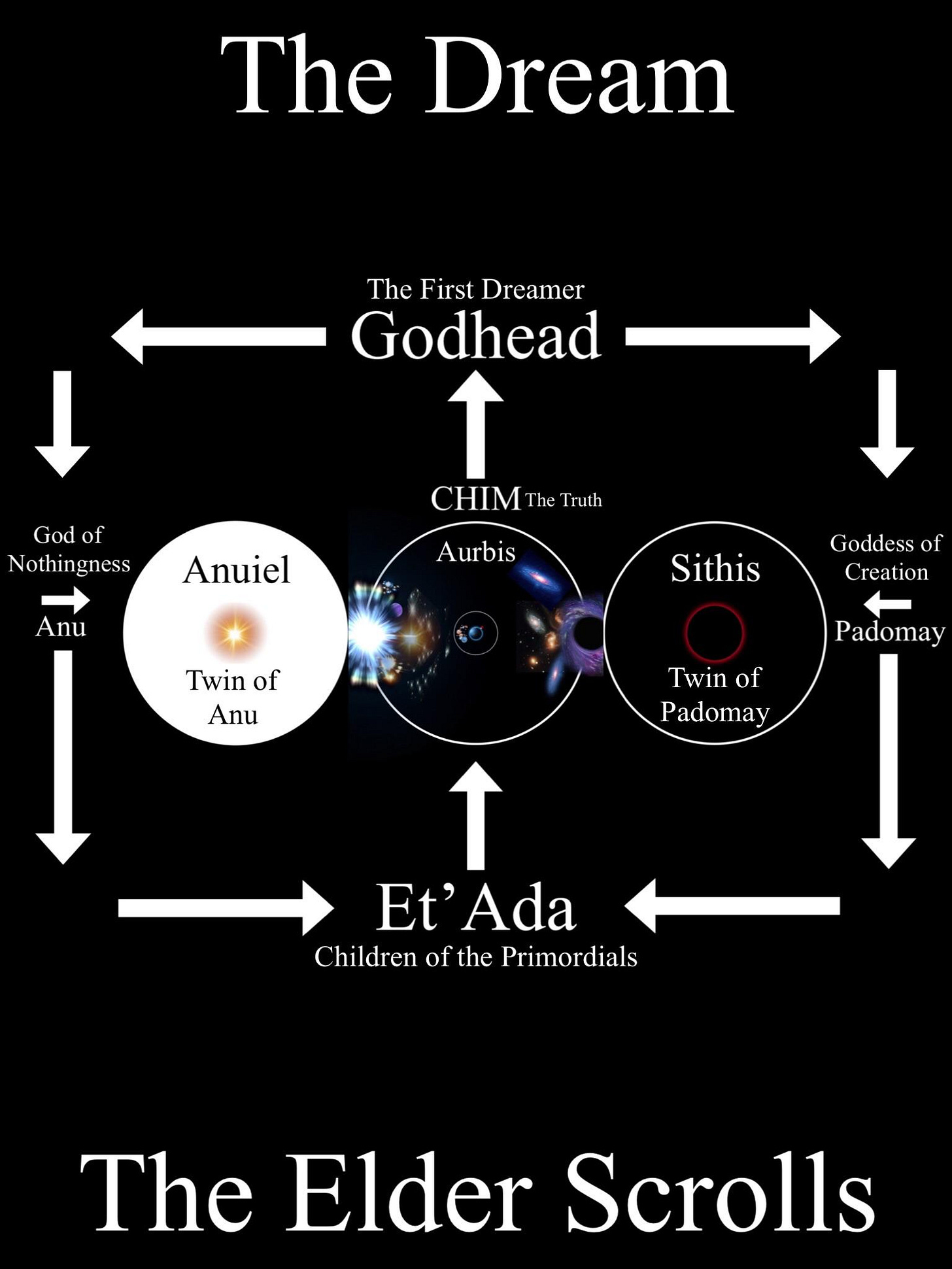

In-game, there is a lore book, The Monomyth (obviously a reference to Joseph Campbell) which describes the common, universal elements present within the religions of Tamriel. In it, we learn that there are only 2 gods present in every race’s pantheon, referred to as “archetypes.” These are the god of time, Akatosh, and the trickster god, Lorkhan, also called “the Missing God.” Lorkhan’s lore is riddled with complexity; he is said to have deceived the et'Ada, or original spirits, into the creation of the mortal plane, Mundus, depleting their power in the process.

The Aedra, the gods, had their power drained to create the mortal plane. They died and took other forms so mortals could live. They stay within the mortal plane to protect it and promote stability, and it is insulated from outside forces. But, in actuality, they are less powerful than the Daedric princes. The domain of the gods is the mortal plane, which, as previously stated, is surrounded on all sides by Hell.

Hell, whose inhabitants are constantly trying to break in.

As punishment for his trickery of the gods, Lorkhan is sentenced to wander the mortal plane. The gods rip out his heart and toss it far away, where it lands on the ground and grows a volcano, which is called “Red Mountain.” The heart would remain in Red Mountain until the Dwemer would discover it and use their technological prowess to try and harness its power. An inventor named Kagrenac created tools to use its power, which would later become very relevant to the history of the Dark Elves.

Planes of Oblivion

The Planes of Oblivion, described in the lore book On Oblivion, are part of the broader, void realm known as “Oblivion.” Although during TES IV: Oblivion, and previously in this essay, Oblivion is called the “demonic realm,” On Oblivion takes pains to clarify that the Daedra are not demons but rather “strange, powerful creatures of uncertain motivation.”

The Planes of Oblivion contain various lands or dimensions within the larger scope of Oblivion. Oblivion is a parallel, transcendent reality that encompasses all existence outside of the mortal plane. The planes, also called “spheres,” have been noted as each being ruled by a Daedric Prince. This rule goes beyond dominion and seeps into the nature of the plane so that each plane is as unique as the temperaments of the Princes. There are only sixteen known Daedric Princes, which vary greatly in how demoniacally they’re portrayed.

Molag Bal is the worst and the closest in temperament and appearance to our colloquial idea of the Devil. Importantly, Coldharbour is not only understood from lore books, but players can experience it firsthand in the 2nd Era setting of TES: Online. The player is sacrificed and trapped in Coldharbour, the prison of the damned, and has to team up with some heroic characters also trapped there in order to escape. This escape is a deviation from traditional Christian soteriology—the player is not bound in Hell eternally. They have means, so long as they are sufficiently brave, knowledgeable, and collaborative, to escape.

In the Shivering Isles, ruled by the Daedric Prince of Madness, Sheogorath, there is a cultural divide: the region called “Mania” is a colorful and vibrant representation of creative madness, while “Dementia” is a dark and brooding representation of paranoia and fear. Throughout the historical development of “Hell,” there is certainly room, categorically, for a sphere of it to resemble the region of Dementia. However, Mania has oscillated toward the positive, and is a far cry from colloquial and traditional depictions of Hell. In fact, the notion of creative potential deriving from madness has a decidedly Jungian air to it. The Shivering Isles broadly, and Mania specifically, are a category shift from tradition; TES has placed them within its version of Hell, yet has borrowed no familiar Hellish imagery or even themes. This depiction of Hell complicates things, encouraging players to think, “Oblivion can be both bad and good, depending on the temperament of the ruler of the plane.”

The player has opportunity to journey to Oblivion a handful of times during the series, but the trip to Coldharbour in TES: Online and the trip to Shivering Isles in TES IV: Oblivion are the greatest journeys, both from a time-in-game perspective and from a lore-relevance one.

In TES: Online, Molag Bal has launched chains from his plane of Oblivion into Mundus in order to drag the mortal plane into his plane. The player visits his realm, explores it, escapes it, and begins a journey to thwart Molag Bal’s plans, which were among the most significant events of the whole 2nd Era.

In the 3rd Era, the invasion of Mehrunes Dagon through the so-called “Oblivion Gates” was undoubtedly the defining event, or so the history books would say.

However, the player’s adventure in the Shivering Isles would have a great effect on the metaphysical plane. By the end of their time there, the player will have “mantled,” or embodied and transformed into the new Sheogorath, transcending mortality and becoming the ruler of Shivering Isles.

Hopelessness

While the pit, Gehenna, in Orthodox Judaism is a place of temporary confinement, the eternality of Hell is the norm in Christianity. Fundamentally, whether it is portrayed with flames, ice, a wasteland, or simple darkness, a fundamental characteristic of Hell is hopelessness.

The agency the player has during their journeys into Oblivion, coupled with the transformative power both for the player and for the cosmos that results from those journeys, is incompatible with the Hell of Christian tradition.

The Hell of TES is no longer a place of hopeless, eternal desolation, and torment. TES has made it a complex and nuanced place, a place of potential, with the capacity to be turned toward either good or evil. Even if trapped there, the player can find a means of escape.

Further, there is even an opportunity to transcend and transform both the fundamental nature of the player from mortal to immortal and send shockwaves throughout the cosmos. There is one other lengthy journey the player takes to Oblivion that exemplifies all of these traits most comprehensively.

In TES V: Skyrim’s “Dawnguard,” the player must journey to the Soul Cairn. The Soul Cairn has already been mentioned as being the plane that is under the dominion of the Ideal Masters, former mortal necromancers whose plane is dedicated to storing captured souls. The Ideal Masters, take the form of giant purple crystals, and their power within this plane is, apparently, absolute—or at least as absolute as that of the Daedric Princes who rule other planes. The souls that make their way to the Soul Cairn are those which have been “soul-trapped,” a process by which a soul is bound to a crystal, called a “soul gem,’ via either enchantment or a spell. This process is the basis of the entire school of Enchantment, whereby all weapons and armor can be enchanted using these soul gems. Once bound to a soul gem, the soul is transported to the Soul Cairn eternally.

The trip to the Soul Cairn confirmed multiple ideas about the nature of metaphysics in TES.

First, mortals could indeed seize planes of Oblivion for themselves, and if they did, the planes could then be transformed in their image, just as they would be for a Daedric Prince.

Second, mortals could fundamentally change their nature from mortal to immortal, and even their bodies—something we knew was possible from the mantling of Sheogorath, but here we learned it was possible as a product solely of the will and efforts of the mortals.

Third, the horrifying background of enchanting, which has been done all across Tamriel for ages – a testament to the possible heights of power and effect that ambitious mortals could achieve.

The threads of New Age spirituality and individualism manifest in these journeys to Oblivion. Hell, traditionally formulated, has been rejected. But it has been retained as a category, and its contents have been broadened to align with the backcloth from which it emerged.

That backcloth has little room for a place of hopeless, collective entrapment and desolation. The desolation is fragmentary, part of a broader context that is rooted in potential. Within that potential, there is room for agency, ascension, and transformation both of the individual and the cosmos.

CHIM

Shifting attention to Morrowind, home of the Dunmer, we find Red Mountain, and within it, the heart of Lorkhan along with Kagrenac's tools designed to utilize its power, resided. Three Chimer (predecessors to Dunmer): Sotha Sil, Almalexia, and Vivec, access the Heart's power using these tools, becoming living gods and deviating from the stern warning of the Daedric Prince, Azura, whom they had previously worshipped as one of the 3 “good daedra.”

They formed what was called “the Tribunal” and called on Morrowind to worship them. They challenged Daedric authority and influence, calling the good daedra the mere “anticipations” of the Tribunal. This blasphemy offended Azura so much that she cursed the race with grey skin and red eyes, turning them from the golden Chimer to the grey Dunmer, the Dark Elves.

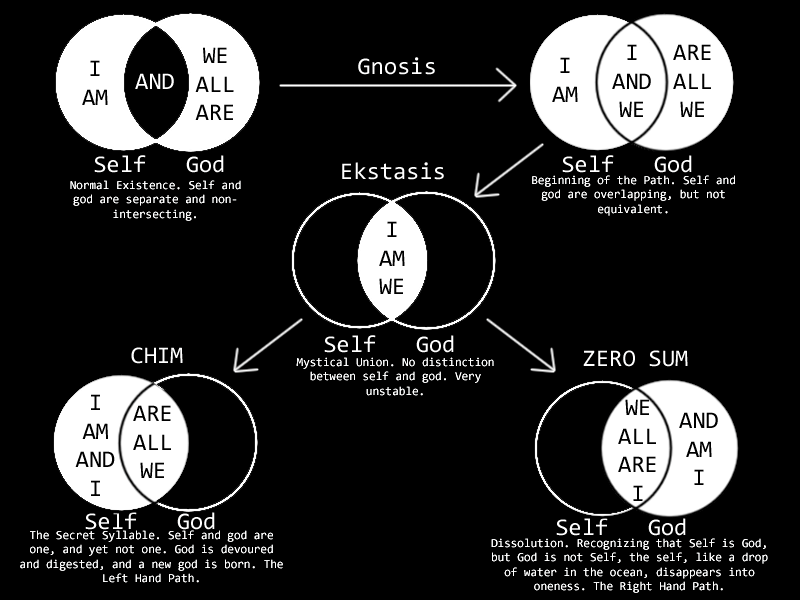

From the Tribunal, Vivec, the Warrior-Poet, was the one most concerned with the legitimacy of his godhood in the eyes of the Dark Elves. He wrote a series of tractates about spirituality called The 36 Lessons of Vivec, wherein he reveals a concept that has fascinated the community of TES since its inception. This concept is CHIM: an overarching cosmic principle suggesting that all beings are mere figments of the Godhead's dream, even the gods themselves. This notion is present in part in various real-world schools of thought, resembling in part Brahman and Maya, Platonism and its successors, especially various versions of gnosticism. These would come to influence Western Esotericism and the New Age, which would also engage Hermeticism, Kabbalism, and the like. In the end, the cosmos is painted as a malleable, illusory thing to be transcended.

Achieving CHIM is no trifling act. It’s a form of gnosis. A common misunderstanding of “gnosis” is that it’s simply “special knowledge” or “secret knowledge,” as though gnosis were a matter of mere intellectual assent. As though a Master Mason or Ascended Master ought to write an insight on paper, hand it to their successors, and suddenly everyone becomes enlightened. This is, unfortunately for acolytes, not the case.

The “secret knowledge” of both gnosis and CHIM involves not only intellectual assent but true, deep understanding. For CHIM, a person cannot simply believe intellectually that reality does not exist; they must internalize that fact. When they do, it leads to one of two outcomes: vanishing into non-existence or ascending to a divine state beyond all constraints. This is a complex concept that I believe has been best expressed by a YouTube loremaster named “Fudgemuppet,” who gave the following analogy:

- You exist, so say you are 1 being.

o You come to accept that you do not exist, so subtract 1 being.

§ This is equivalent to 1-1=0

- With CHIM, you accept that you do not exist and still assert your own being.

o This is equivalent to 1-1=1

CHIM is internally paradoxical, like a Buddhist koan, and allows the individual who achieved it to transcend all planes entirely, becoming a godhead themselves. This feat was potentially accomplished by Vivec and almost certainly accomplished by the Nord god Talos. When the achiever of CHIM exits the Matrix, effectively leaving Plato’s cave, they can manipulate it as they see fit, just like Neo from The Matrix. They are outside of all Aedra and Daedra, so even time is under their control. Talos used this power to change Cyrodil, heart of the Empire. Cyrodil was once all jungles, yet when it is explored in TES IV: Oblivion, it is a conventional fantasy landscape with plains and forests. Then, Talos changed the timeline so that, although prior to his ascension, it was all jungles, it now has no jungles and never did.

The cosmology of TES is already a unique inversion of traditional cosmologies that have supplied colloquial images of Hell, but through The 36 Lessons of Vivec, we come to learn that the foundational truth lies even outside of that.

The transformations of Hell in its representation as Oblivion included nature, contents, themes, and narratives. But Vivec offers the ultimate transformation: a transformation of context. Neither Hell nor Heaven are fundamental; the most fundamental is the dreamer. The mantling of Sheogorath, the ascendence of the Ideal Masters, and even the Tribunal becoming living gods, were nothing more than hints of the true potential of transcendence that could be achieved.

This transcendence has allowed to individuals, both born mortal, to step outside of the theodrama of Aedra and Daedra, Mundus and Oblivion, and manipulate them at will.

Conclusion

At the heart of The Elder Scrolls series is the individual’s journey toward personal empowerment and transcendence. This is displayed in gameplay, yes, but is also both implicit and explicit in the lore. This affects everything within the lore, including its portrayal of Hell, Oblivion. The demoniac realms surround the mortal plane from all sides, peopled with powerful, immortal entities, some of which wield immeasurable power.

Despite all of this, mortals can ascend. The transformative journey essential to New Age spirituality, facilitated by individualism, calls on the player to accept no limitations. Mortals can become Daedric Princes, they can seize on the potential of Oblivion and claim a sphere for themselves, they can even become living gods. Then, if that’s not good enough, they can even go beyond godhood, stepping outside of the cosmos itself and becoming new dreamers.

The backcloth that TES drew from is one where institutionalized religion is present in many forms, each of which gleaning only a part of some great truth that can be grasped by an individual with sufficient motivation. There are multiple religions in Tamriel with multiple pantheons, most worshipping the Aedra. Each of these, however, must grapple with the knowledge that the Aedra can only protect them because the mortal plane holds Oblivion at bay. There are known entities in Oblivion with both the power and motivation to overtake mortals, and there are likely infinitely more entities whose motivations and powers are unknown. But, in the end, this constant spiritual tension is contained within a dream.

The eclectic grabbing of spiritual practices and beliefs by the New Age is acceptable because, fundamentally, its practitioners do so as believers in the fundamental truth: there is no Hell, even if there are Hellish planes of existence, and the individual can transcend those planes.

Those who have seized power in Oblivion have experienced a glimpse of the reality-shaping power of consciousness. They have, in the parlance of New Age spirituality, tapped into the power of the Law of Attraction. The telos of which being a full transformation and ascendence of the individual, leading to a transformation of the cosmos, exemplified in TES by CHIM.

TES is an expression of contemporary spirituality and its modulation by individualism and personal agency. As such, it’s no surprise that its portrayal of Hell demanded a unique reinterpretation as a potential realm of self-empowerment and personal transcendence. Where a traditional depiction would set Hell as a place of eternal torment, the Hell of TES should be perceived by real-world loremasters and in-game citizens alike as a place of potential and discovery.

Wrought with evil, certainly, but not inherently so. It is, in fact, only a part of the whole story, a story where the individual can conquer reality itself.

![The Battle Of Red Mountain-[I]The Battle of Red Mountain was a battle that marked the culmination of the War of the First Cou The Battle Of Red Mountain-[I]The Battle of Red Mountain was a battle that marked the culmination of the War of the First Cou](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!6k1S!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ffc548609-c3aa-4e2a-bb06-46303f559d89_720x409.jpeg)

I played these games a little, a long while ago, but clearly nowhere near enough to understand the deeper levels of what was going on. A very interesting dive, here.