Make Animals Monsters Again

Stealing the Blue Whale’s Mythic Power

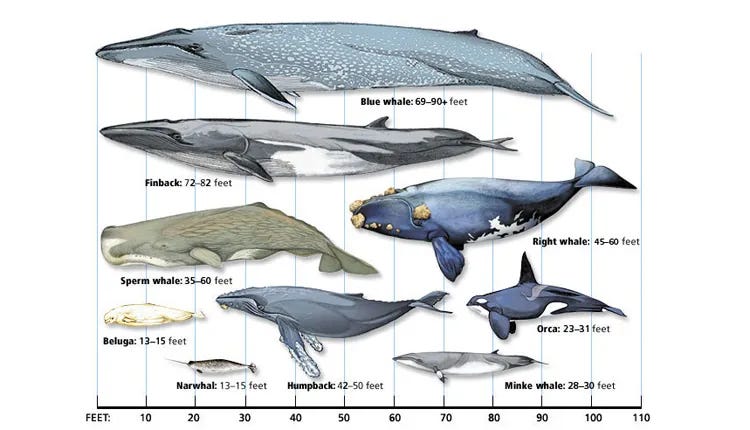

I saw a video of a blue whale the other day and it sent me down a rabbit hole. I enjoyed marine life quite a bit as a kid, so part of the reaction was nostalgia, which is perfectly fine. But the other part of the reaction was awe. Those dang things are big.

They're way, way too big. Plus, they look like they belong on another planet. On top of that, they spend their time submerged in the darkness of the ocean.

If I didn't know what I was looking at—if it were just a shadow passing under me—I’d be terrified. That seems to me to be a sea monster. But it’s not.

I don’t contend that, historically, blue whales were regarded as sea monsters. I’m actually not sure what history has to say on the subject. I know that Mycenaeans were familiar with dolphins, but, to my shame, my historical whale knowledge is sorely lacking.

Rather, I want to speak more to the sort of cultural imagination that allows us to think of something as a monster. And our current cultural imagination thinks of a monster as a thing from myth or legend—unfamiliar, uncontrollable, terrifying, and probably ferocious. The blue whale, while huge and strange, no longer belongs to that category. We know what it is, and we’ve studied it extensively. It’s been pulled out of myth and into fact.

Now we might say, it’s not because of our knowledge of it. It’s because the blue whale is itself gentle. Certainly that’s why it doesn’t scare us.

But if we didn’t know that, if it were just a shape in the water, it would certainly inspire terror. That’s hardly controversial. So, the gentleness matters, yes, but knowledge precedes comfort. What calms us is not the whale’s temperament, but our confidence in its familiarity—temperament included.

At this point, someone might object. Sure, the blue whale is gentle, but not all whales are—which is true. Here we might consider the sperm whale. Herman Melville did his part to preserve its mythic status. Moby-Dick was less an animal than a metaphysical event. But, if SeaWorld Orlando announced that it acquired a sperm whale, I doubt many people would be shocked. Sure, we might have some logistical questions about tank size or transport, but not existential awe. Few would question how a human being—or team of human beings—were able to capture such a thing.

Point being, we no longer think of these creatures as untameable, and it’s not because they’ve changed. It’s because we’ve changed, and as a result of our change we no longer treat them as monsters.

Terrors of the Deep

Let’s be honest: the public’s understanding of marine threat levels is conditioned, in no small part, by Shark Week. And the king of Shark Week is the great white shark. That’s the pop culture apex predator, and for good reason. They don’t have very many natural predators—but they do have some.

The non-whale killer whales, orcas, hunt great white sharks. So, at least when in a pod, orcas are the apex predator of the sea and ought to be regarded as such.

Yet far from representing some existential dread, they perform tricks for crowds at SeaWorld. Tricks including and up to allowing a human being to step on their nose and do a flip.

Yes, there are exceptions. I’ve seen Blackfish too. But as a general rule, parents don’t tend to cover their children’s eyes when a trainer rides on an orca’s nose. They point. They cheer. They say ooh, ah, rather than oh no, watch out, someone please stop them! And that is not how we treat monsters.

So then—what is a monster?

At first glance, it might seem like it’s the captivity that quells the monsterhood of the killer whale. That if only it had freedom, its lethality would fashion it into some kind of monster.

This seems to be getting closer to the truth, but still doesn’t seem to be the whole story.

A great white shark outside of captivity is certainly regarded with fear, but not with that existential dread. Take the kraken; this is a much more tangible example because the giant squid—or even worse, the colossal squid—was part of our ancient mythology. They existed in our cultural imagination purely as monster, and as such were relegated to the realm of myth. Never likely to emerge as a physical, flesh-and-blood animal.

Until they did.

And once they did, they left the realm of monster and became part of the realm of animal. Which is, in part, a tragic thing.

Did the giant squid or the colossal squid become less dangerous once captured on video? Did they become smaller somehow?

Yes, perhaps smaller than some of the legends—but certainly large enough to be something like a legend. Its capacity to overwhelm a human, or possibly even a ship, didn’t vanish. If anything, the footage should have confirmed how alien it still is.

But instead, something else changed: the symbolic register.

It’s no fault of the squid that we exaggerated its abilities in our myths, and it’s certainly not the squid’s fault that we redacted those exaggerations later on. The creature remains what it is. The change happened in us. We lost the sense that this being hovered outside the boundaries of our understanding.

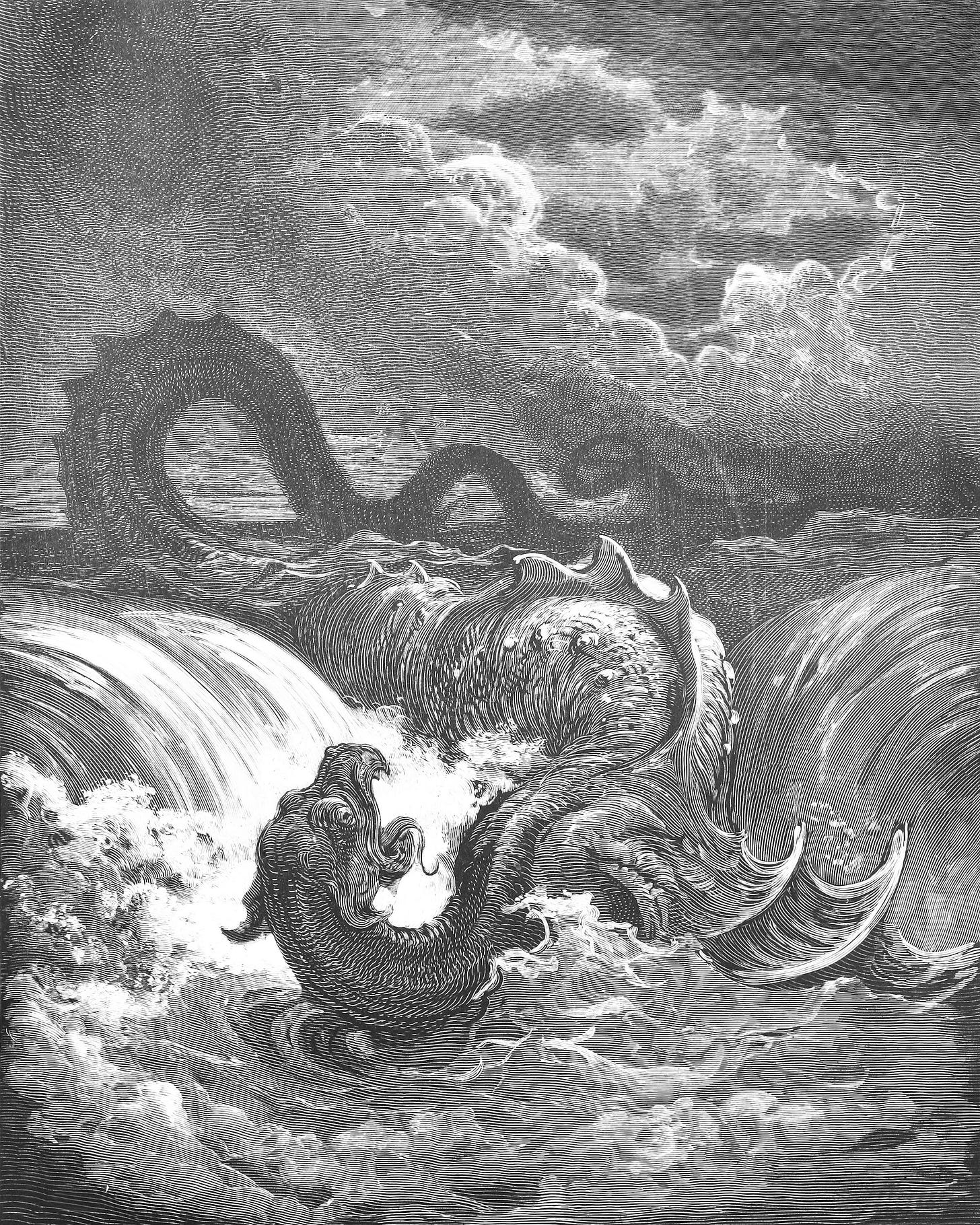

Say, for the sake of argument, that we discover Leviathan—real one. A massive serpent dwelling deep in the ocean trenches, larger than any known species. For a week, maybe two, it would certainly dominate global headlines. The biblical Leviathan has been found. Or, Is this the source of the world serpent? And we might conclude that it was. Then we find out that it’s not spiritual, that it can’t threaten humanity in any serious way, that it can be killed, and it’s just a big snake.

Quickly enough, the news cycle would move on. Sure, there’d be pockets of investigators who never give up the good fight, but they’d be on the fringes again, desperately trying to attach some mythology to it. But for the rest of society, those guys will have long been boxed out by the folks doing the real work; marine biologists and such. Those wielding authority to anoint things as known, and therefore part of the territory gained in man’s conquest over nature.

Of UFOs & UAPs

We’ve seen the cycle of subsummation occur in real time, and with a far greater existential threat than squid. The United States Air Force did research on unidentified flying objects in the 1980s under the name of Project Blue Book. It determined, after examining several cases, that most could be chalked up to some natural phenomenon like swamp gas or known aircraft or simple error on the part of the observer—and thus there was nothing worth looking at.

Since then, the narrative was that the United States government simply ceased funding research into the UFO phenomenon (now called the Unidentified Aerial Phenomenon or UAP) because it wasn’t worth looking into.

Then, in 2020, they admitted that this wasn’t true. They admitted that they still did research in this area. The Pentagon even released a video that caused quite the stir online. Did you know the organization that negotiated the release is headed by Tom DeLonge of Blink-182, and they’re still around doing the same work? If you’re not part of the UFO/UAP community, there’s a good chance you weren’t aware.

I’d wager that, collectively, we’ve all raised the threshold for what’s normal, and decided UFOs/UAPs are part of that threshold. Now, those same things once dismissed as conspiratorial nonsense are assumed to be a real, probably not swamp gas, phenomenon. No longer can Neil DeGrasse Tyson say that it’s only ever non-credible witnesses because they don’t know what they’re looking at. The argument has shifted—well, that doesn’t prove aliens are real. Of course not! But weren’t we all wondering if UFOs/UAPs were intelligently operated, unknown craft for the last 80 years?

The novelty, it seems, is when the phenomenon is in our periphery, not yet at the point of confirmation.

We might speculate that even if intelligent alien life were confirmed tomorrow, the same cycle would repeat. There would be fascination for a time. But suppose they stopped in and said:

"Hi. We’re aliens. We’ve been observing you for a while. We live a few galaxies away. We’ve mastered gravity-based travel. We had nothing to do with your creation or your evolution. We’ve only been here for a few hundred years. And we haven’t run into any other alien species on the way. So we’re leaving. Bye."

We would spend a few news cycles talking about them. We would certainly reference it as a watershed moment later on. But, ultimately, the visitors would go into the category of the known, and we’d refocus on the next unknown.

Well, they were a bit boring, but probably there’s some big existential crisis lying somewhere else in the universe. I mean, those aliens claim to be the only ones, but what are they really hiding?

We’d have to craft mythology just to feel captivated, because it’s the unknown which holds power over us. This is no surprise; this is why mystery stories capture our attention. Here, however, a bit of a distinction is necessary.

Spooky Ghosts

Consider another example. If somebody were to put on a ghost movie for you, and in the movie, a family moved into a new house. Then, they witnessed no paranormal events or inordinate drama. They woke up and went to school and work, had a couple of meals, lived in the house comfortably over the course of a few months, and then the movie ended.

The one who asked you to watch it approaches and asks, “Were you terrified?”

You might say, “No, of course not. But I guess it was kind of a nice slice-of-life thing?”

They say, “No, no, there were ghosts all around!”

You’d say, “Then why didn’t anything happen?”

They say, “Well, the ghosts didn’t interact with the family. They stayed in their space. But they were certainly there, right in frame.”

You’d say, “That’s not how you make a ghost movie.”

This is because the unknown as pure absence, as pure Other, with a capital “o,” doesn’t become a monster until it encroaches on our world. Until it breaches the mundane while still keeping at least part of itself in the shadows.

A monster exists as a partially understood phenomenon that refuses resolution. Not invisible, but never fully revealed. It lives in a liminal space between what we can name and what we can’t. It is this ambiguity that gives it power over us.

This is why a horror film often collapses when they reveal the monster too early. It stops being something that plays on our subtle fears, and becomes something that relies on action sequences and jump scares.

Thus, a monster seems to be a being that threatens the boundary between the known and the unknown, resisting proper categorization. This resistance threatens not only to frighten, but to destabilize. To destabilize a chunk of (or significant portion of) our epistemological scaffolding.

This seems to serve as a reminder for us that the scaffolding is both fragile and hard-won.

Indeterminacy & Naming

We can find interest in this topic, though expressed with very different terms and intent, across traditions. For Barth, the Wholly Other provokes awe and dread precisely because it exceeds the frame of human comprehension. It is that which is incomprehensible. Gregory of Nyssa would call such things apophatic. They can only be described by what they are not. More recently, Jordan Peterson would use the word chaos in his popular work as a stand-in for the unknown, but in his academic work, he would call it indeterminacy—which is contrasted with determinacy, our ability to bracket things psychologically.

Think of the book of Genesis. Adam is tasked with naming God’s creations.

“So out of the ground the Lord God formed every animal of the field and every bird of the air, and brought them to the man to see what he would call them; and whatever the man called each living creature, that was its name.” (Genesis 2:19)

In ancient thought, to name was not just to describe, but carried implications of dominion. Names held a power over the thing named. To be entrusted to name creatures on earth was a great role, casting Adam and the rest of humanity, as above the creatures in stature, in a class all our own.

This is why so many exorcists seek to find the names of demons. This is why we’re told not to take the name of the LORD in vain.

It’s worth pause here to note that anyone seeking to apply psychological principles to the study of history would do well to tread cautiously. This is a great way to eisegete modern biases into the past. We ought not, therefore, determine that the formulation that follows is definitive or comprehensive. That said, it seems that one reason for this power of naming is because, partially, to name something is to bring it into the domain of the known—to frame it, and in doing so, to strip it of its mystery.

So in a way, classification might be thought of as a form of mastery, which comes with a cost.

When we name the thing, we take away some of its mythic potency. We continue to chip away as we learn & categorize more things about it. What we’re left with is something we can study. Something we can track, teach about in school—apprehend. But it just doesn’t haunt us in the same way.

Which, in many ways, is a good thing. I certainly wouldn’t be keen on worrying about dragons every time I walk in an open area, nor about the Leviathan if I ever go on a cruise.

But it might not be so good. Who can say the long-term social impacts of certitude that there are no more monsters? Maybe, and I hesitate to write this line because it’s such low-hanging fruit, maybe we become the monsters.

Either way, I feel bad for the blue whale.

This is really interesting, and so beautifully written!

I have many favorite parts, but this is one of them: "When we name the thing, we take away some of its mythic potency. We continue to chip away as we learn & categorize more things about it. What we’re left with is something we can study. Something we can track, teach about in school—apprehend. But it just doesn’t haunt us in the same way."

I think it goes hand in hand with all the "villain origin story" treatments of classic stories, too. Where they used to depict a monstrousness which must be vanquished or overcome, they now showcase a monstrousness which must be understood.